Campo de Cahuenga

3919 Lankershim Boulevard – map

Declared: 11/13/64

Campo de Cahuenga marks the site where the Treaty of Cahuenga was signed on January 13, 1847, effectively marking the end of the U.S.-Mexican War and turning over Alta California to the United States. (The formal ending came with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the following year.) Leading the signers to the 1847 agreement were U.S Lieutenant Colonel John Fremont and Mexican General Andres Pico.

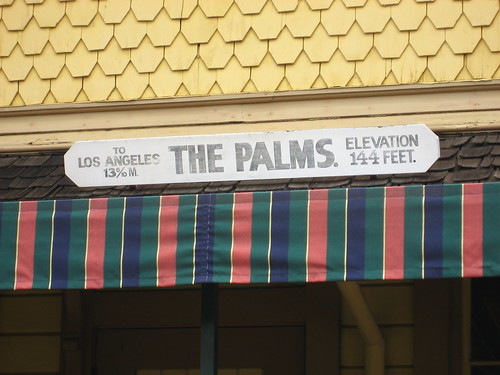

Another El Camino Real Bell.

The original adobe farmhouse in which the treaty was signed deteriorated and was torn down more than a century ago. That building was built probably between 1785 and 1810.

The city bought the site in the 1920s and built another adobe there, dedicating it in 1950. The front of this current building mirrors the original’s.

Flash forward to the mid-1990s as the Metro Rail Red Line subway was being dug there on Lankershim Boulevard. Workers uncovered the original house’s foundation and floor tiles, some of which have been preserved and are on display.

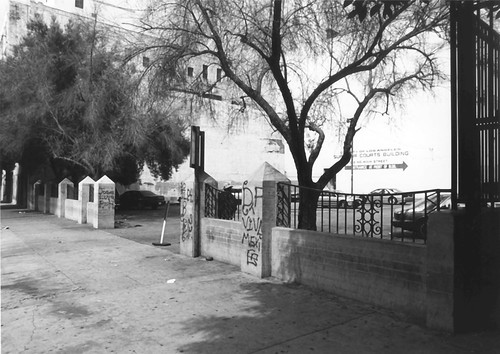

Unfortunately, Campo de Cahuenga’s open just a few hours a week – only on Saturdays. But that’s when it is open. Which it’s not, now. I’m told the site will be open again “toward the end of the year”. So no look inside at the museum part, for now.

Until the re-opening, you can look through the gate bars at the new building. On Lankershim, you can see the fancy paving and brickwork denoting the location of the original building, which measured about ten by forty feet. You might be driving over it every day and not even know it.

The outline of the original adobe on Lankershim Boulevard.

Here’s the official webpage for Campo de Cahuenga. The site’s also on the National Register of Historic Places, and is designated California Historical Landmark No. 151.

Where are those L.A. blue skies?

Up next: Doheny Mansion