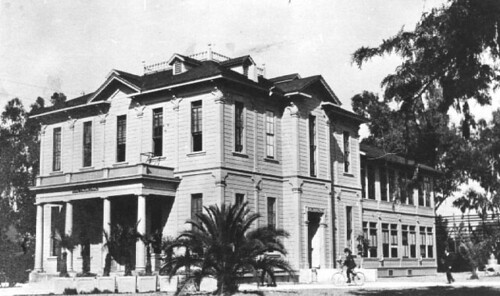

Widney Hall

1880 – Ezra F. Kysor and Octavius Morgan

650 Childs Way – map

Declared: 12/16/70

USC’s Widney Hall is Southern California’s oldest university building.

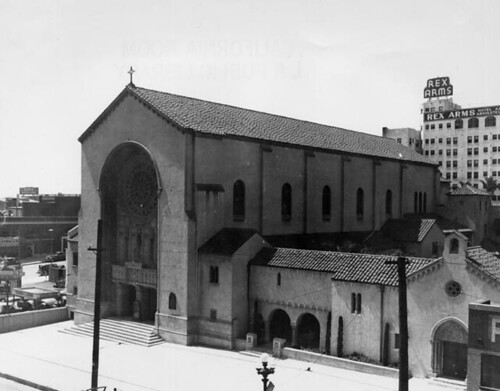

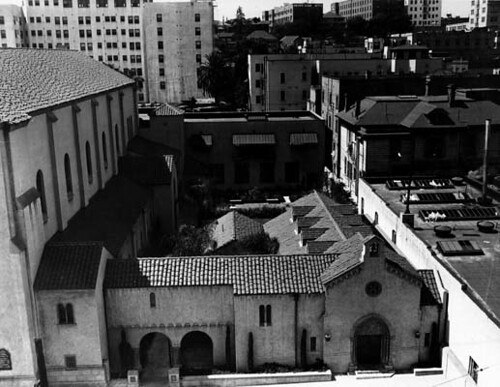

Widney Hall's initial Italianate design.

The state’s dedication plaque (Widney Hall is California Historical Landmark No. 536), from 1955, gives about as much information as I plan on digging up here.

“Dedicated on September 4, 1880, this original building of the University of Southern California has been in use continuously for educational purposes since its doors were first opened to students on October 6, 1880, by the university’s first president, Marion McKinley Bovard. The building was constructed on land donated by Ozro W. Childs, John G. Downey and Isaias W. Hellman under the guiding hand of Judge Robert M. Widney, the university’s leading founder.”

It's one thing for the later addition of the porch not to survive, but that back portion is gone today, too.

After being moved around campus a few times, and after undergoing a few design changes (as seen in the black and white shots above and this green-shuttered incarnation), Widney Hall was restored in 1977 by Gin D. Wong Associates to a fair representation of how the building originally stood nearly a century before. (Thanks to the Public Art in L.A. website for the restoration’s year and architectural firm.)

The back, or north, side.

Now called Widney Alumni House, this old building is currently the home to USC’s General Alumni Association.

Finally, this is probably the only single post I’ll write including the names Ezra, Ozro, Octavius, Isaias, and Marion (for a guy), so soak it in.

Up next: First African Methodist Episcopal Church Building