Thursday, May 29, 2008

No. 148 - Coral Trees

Coral Trees

San Vicente Boulevard between Bringham Avenue and 26th Street, Brentwood – map

Declared: 3/3/76

I didn’t count them all, but there sure are a lot of coral trees on this nearly two-mile stretch of San Vicente Boulevard in Brentwood.

Of course you knew the Erythrina is the official tree of the city of Los Angeles. Actually, I should say the Erythrina are the official tree, because there are about 130 species of them, most commonly known as coral trees. The city’s designation of officialdom includes all of them.

Why Los Angeles Beautiful and Valley Knudsen recommended this tree – a tree that originated in South Africa – to be our official tree, I don’t know. Then-mayor Sam Yorty, at the declaration on Arbor Day in 1966, praised the tree as “smog resistant and relatively pest free.” He went on to say the coral tree was chosen for “its beauty and versatility and in keeping with the city’s Spanish and Mexican heritage.” Huh?

Here are some native L.A. trees that missed out on the title: the California Black Walnut; the Western Sycamore; the Coast Live Oak; the Valley Oak; and the California Bay. (By the way, all of those trees are protected in the city of L.A. under the Native Tree Protection Ordinance. You need permission from the Board of Public Works to cut down any. So, watch out.) Me, I would’ve chosen the Coast Live Oak, but I digress.

The species of Erythrina you see on San Vicente is the caffra, AKA the Kaffir Coral Tree AKA the Coast Coral Tree. The word erythrina comes from the Greek word for red. Caffra is Arabic, and means unbeliever. I could write a long post about the E.c., but I’d take nearly everything from this site. Go there and read about both the tree’s medicinal and poisonous qualities and decide which parts you want to recommend to your mother-in-law.

Below are two pictures, one of the eastern end of the monument at Bringham, the lower at the western edge where 26th Street crosses San Vincente.

Just a few of the trees on San Vicente were sprouting flowers when I was there. If those trees bloom at the same time, it must be something to see.

Oh. L.A.’s official flower is the bird of paradise, also a native of South Africa.

Sources:

“L.A. Adopts Flowering Coral Tree” Los Angeles Times; Mar 8, 1966, B16

Atkinson, Robert E. “Our City Adopts a Tree of Flame" Los Angeles Times; Jun 12, 1966, p. 24

Up next: Ennis-Brown House

Monday, May 26, 2008

No. 147 - James H. Dodson Residence

James H. Dodson Residence

1880s

859 West 13th Street, San Pedro – map

Declared: 9/17/75

Moved a bunch of times over its 1.2 centuries of existence, the old James H. Dodson residence is now pretty much blotted out by trees, bushes, shrubs, and more trees. Some of its history is a little obscured, too.

James Hillsey Dodson’s bio lists gigs in the building supplies and contracting business with his brother John and as a junior partner in the meat-packing firm of Vickery & Hinds. He was also a member of the San Pedro School Board, Director of the First National Bank, and San Pedro’s postmaster between 1893 and 1897. If that’s not enough, Dodson twice served as president of the San Pedro Board of Trustees, the precursor to the City Council.

From 1930, that's James H. Dodson on the right. The quintet is clearly celebrating the birthday of Methuselah, standing next to Dodson. Photo from the L.A. Public Library.

In 1879 or 1881, he married Rudecinda Sepulveda (b. 1857), the daughter of Maria Elisalde and Jose Diego Sepulveda, owner of the 3,200-acre Palos Verde Rancho. If not quite royalty, Rudecinda and Dodson – a descendent of the Dominguez clan – were certainly at the center of the social world of early San Pedro. It’s said the Sepulvedas built this twelve-room, two-story Victorian house with its three-way fireplace as a wedding present for the young couple. I’ve seen constructions dates of 1881, 1882, 1885, 1886, and even 1890. From USC's Digital Archive, Rudecinda:

In any event, the home was built on Sepulveda property at the northwest corner of Beacon and 7th Streets on the edge of Vinegar Hill. Just after the turn of the century, the Dodson Residence was moved to another plot of Sepulveda-owned land, roughly bounded from Leland to Meyler and from 15th to 17th Streets, school land today.

To accommodate the needs of the growing high school, the house was relocated in the mid-1930s a few blocks to the north side of 13th Street. After a short time, it was moved again, this time to its current site at 13th and Parker. Here, it took on life as a rooming house. (Rudecinda died in 1929; James moved out in 1931, dying eight years later. They, along with their children – Carlos, Florence, and James Jr – are interred in the Rudecinda Crypt, part of Historical-Cultural Monument No. 53.)

John and Betty Reed bought the house in 1954 and began a decades-long restoration of the old home. The grand Victorian remained in the Reed family as late as 1989. I don’t know who lives there now, but, whoever it is, they sure like shade.

Sources:

Vickery, Oliver “The Dodson House Restoration” The Shoreline Jan 1978, Vol. 5, No. 1

Vickery, Oliver “Rudecinda Sepulveda” The Shoreline Sep 1977 p. 12

Houston, John M. “The Dodson-Sepulveda Home” The Shoreline Jun 1989 p. 47

Up next: Coral Trees

Friday, May 23, 2008

No. 146 - Municipal Ferry Building

Municipal Ferry Building

1941 – Derwood Irvin

Sixth Street at Harbor Boulevard – map

Declared: 9/17/75

Finished in 1941 as a WPA project, San Pedro’s Municipal Ferry Building was one of the pair of terminals for the auto ferry service carrying passengers – lots of military personnel and cannery and shipyard workers – to and from Terminal Island.

The building was the work of architect Derwood Lydell Irvin, born in the early 1880s in Eagle Rock. After studying at Berkeley, Irvin was working for the Los Angeles Harbor Department when he got the assignment to design the ferry terminal buildings at Berths 84 (this one) and 234 (on Terminal Island, demolished in the early 1970s).

Since those two windows have been sealed up, this wall looks ripe for graffiti.

In 1963, the brand new Vincent Thomas Bridge, “San Pedro’s Golden Gate”, made the double-decked ferries – the Islander and the Ace – obsolete. After the Islander’s last run on November 14 of that year, the building became an overflow office for the Harbor Department.

With some re-design work by architects Pullman and Matthews, the old Streamline Moderne building with its five-story octagonal tower has been home to the L.A. Maritime Museum since 1979.

The 'Gosling', built in 1924.

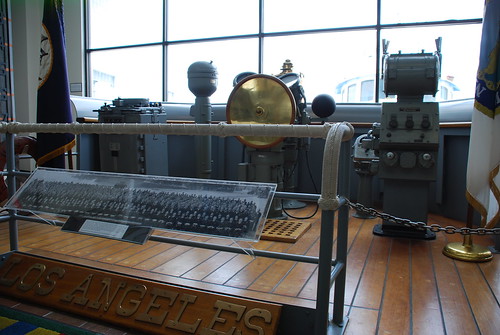

The largest of its kind on the west coast, the museum has all the displays, equipment, and artifacts you’d expect and then some. You can see models of the United States Ships the Los Angeles, the Long Beach, and the San Pedro, in addition to a whole bunch more. Along with the ship’s bell on the museum’s lawn, the Los Angeles’s bridge can be found re-assembled inside.

Here’s a pair of shots looking through a museum back window out upon the Glenn M. Anderson Channel. The first shows the Vincent Thomas Bridge in the background, the second is of the tugboat “Angels Gate”, built in 1944.

At the museum you can watch the radio operators of the United Radio Amateur Club broadcast from the second floor. There’s also the model of the S.S. Poseidon, used in the 1972 movie The Poseidon Adventure. It was built, 1/48th to scale, using the original plans for the Queen Mary. I tried flipping it over to see how long Shelley Winters could hold her breath, but was stopped by security.

San Pedro’s Municipal Ferry Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996.

Sources:

“Derwood Irvin: The Man Behind the Ferry Terminals” Channel Crossings Summer 2005 Vol. 2, No. 1

McKowen, Ken and Dahlynn Best of California’s Missions, Mansions, and Museums Wilderness Press 2006 Berkeley, CA

Up next: James H. Dodson Residence

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

No. 145 - 3537 Griffin Avenue Residence

3537 Griffin Avenue

c. 1886

3537 Griffin Avenue, Lincoln Heights – map

Declared: 5/21/75

Designated an official city landmark thirty-three years ago this week, 3537 Griffin Avenue doesn’t have much of a notable history, or, rather, much of a notable history researchable without me leaving my couch.

Most resources say this home was built around 1886, although ZIMAS says 1910. That latter date is crazy, especially if it’s the work of architect Joseph Cather Newsom (1858 - 1930) to whom some attribute it. Cather designed HCM No. 258, the Fitzgerald Residence (1903), and No. 565, the Greenshaw Residence (1906), in the styles of “Italian Gothic” and Mission Revival respectively, so his reversion to this earlier Queen Anne style at the very end of the Victorian age is unlikely. Not to mention the late 19th-century development time frame of the development of Lincoln Heights. Am I right, America?

Gebhard and Winter tell us 3537 is a “two-story Queen Anne dwelling” with a “double-gabled dormer on the third floor.” Note not only the dormer but also the continuity gaffe in G&W’s entry.

One final thing. While I choose not to believe ZIMAS’s given year of construction, I'll go along with the site's saying this old house is made up of more than 2,300 square feet. Roomy!

(Oh. Whose idea was it to have a sky-colored roof?)

Source:

Gleye, Paul The Architecture of Los Angeles Rosebud Books 1981 Los Angeles

Up next: Municipal Ferry Building

Saturday, May 17, 2008

No. 144 - 2054 Griffin Avenue Residence

2054 Griffin Avenue Residence

c. 1887

2054 Griffin Avenue, Lincoln Heights – map

Declared: 5/21/75

This masonry Victorian house in Lincoln Heights is one of the oldest in the community. The street on which it sits is named for Dr J.S. Griffin, “The Father of East Los Angeles.”

John Strother Griffin was born in Fincastle, Virginia, in 1816. Raised in Louisville, Kentucky, he went to med school at the University of Pennsylvania, and became a doctor in the U.S. Army. As head surgeon for Gen. Stephen Kearny, he not only tended to the injured in the battle of San Pascual in December 1846, he also was on hand for the American capture of the city of Los Angeles the following month. (Buy his diary of his Mexican War experience here.) He returned to settle in L.A. in 1854.

Griffin was interested not only in education – in 1856 he was elected superintendent of the first public school in L.A. – but also in educators – he married Louisa Hayes, the city’s first female public-school teacher. With Prudent Beaudry and Solomon Lazard, he set up the Los Angeles Water Company, obtaining a thirty-year lease to oversee the city’s water system beginning in 1868 (he built the first irrigation ditch taking water from the Arroyo Seco to water the region). Griffin was the first president of the County Medical Society (1871) and served as a director on the city’s first Chamber of Commerce, then known as the Board of Trade (1873). (A lot of firsts in this paragraph. - ed.)

One of L.A.’s early physicians, he bought up land like nobody’s business throughout the 1860s, including two thousand acres in East L.A. in 1863 for fifty cents an acre. In 1873 he sold 4,000 acres of Rancho San Pascual (which he had bought from Don Manuel Garfias some fifteen years earlier) to an organization from Indiana which renamed the land Pasadena.

With his nephew, Hancock Johnston, Griffin laid out and planned the streets of East Los Angeles, selling the land little by little. (It’s ironic a large chunk of his old property is Lincoln Heights. According to Harris Newmark, Griffin was a staunch Southerner who lost his senses cheering Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in 1865.)

Dr Griffin spent many years living on Main Street between First and Second, but died in his home at 1109 Downey Avenue, now North Broadway, on August 23, 1898.

This landmark was built around 1887. Various city directories list residents Joseph and Rosina Thompson and Pearl Treon (1936) and osteopathic physician C.E. Broadhead (1939). Walter H. Klapper owned the house during its designation in 1975, and architect Bruce Boehner and his wife, Gloria, soon after purchased the home with plans to restore it.

It looks to be in great shape today, but I can’t figure out what that solitary second-story window on the north side indicates in terms of the floor’s layout. It looks original to the building’s design, too.

Sources:

“Founder of Cities.” Los Angeles Times; Aug 24, 1898, p. 11

Newmark, Harris. Sixty Years in Southern California Houghton Mifflin Company 1930 Boston and New York

Up next: 3537 Griffin Avenue Residence