Residence of William Grant Still

1262 South Victoria Avenue – map

Declared: 12/1/76

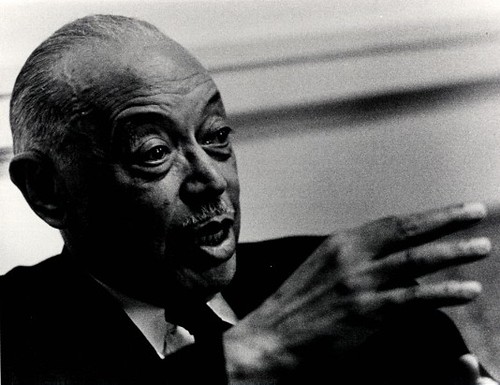

Alright. I’ll ‘fess up. Up until a few weeks ago, I had never heard of William Grant Still. It turns out the “Dean of Afro-American Composers” wrote more 150 musical works, including nine operas, five symphonies, four ballets, chamber works, and so on. He was also an arranger, conductor, and an accomplished oboe player. So I guess I'm the rube.

Actually, it’s pretty tough to summarize Still’s achievements in just this one post. For a much more detailed list of the man’s accomplishments, visit AfriClassical.com (where you can also listen to some brief audio clips) or the official home of William Grant Still Music.

Still was born in Mississippi in 1895, but moved to Little Rock with his mom a few months later after the death of his father.

Personally, I like knowing the guy worked with W.C. Handy, Sophie Tucker, Artie Shaw, and Paul Whiteman. A WWI U.S. navy veteran, he arranged for and/or played in New York City shows including Sissle and Blake’s Shuffle Along and Dixie to Broadway. Still studied with George Whitefield Chadwick and Edgar Varèse in the twenties and received both Guggenheim and Rosenwald Fellowships. He was a member of the Harlem Renaissance and played oboe with the Harlem Orchestra.

The first performance of a William Grant Still classical work was of From the Land of Dreams on February 8, 1925. On October 28, 1931, the Rochester Philharmonic premiered Still’s first symphony, the Afro-American Symphony.

He settled in Los Angeles in 1934. Two years later, on July 23, 1936, Still conducted the L.A. Philharmonic playing one of his works at the Hollywood Bowl. This was the first time an African-American conductor led a major symphony orchestra in concert in the U.S.

Still co-wrote the 1936 ballet Lenox Avenue with pianist Verna Arvey, whom he would go on to marry in 1939 (Verna was Still’s second marriage; he had four children with his first wife, Grace Bundy, whom he divorced). He then worked with Langston Hughes on the opera Troubled Island and with Zora Neale Hurston on Caribbean Melodies. In 1940, the New York Philharmonic performed And They Lynched Him to a Tree, a choral ballad he wrote with Katherine Garrison Chapin.

William Grant Still succumbed to the Hollywood bug, (not always with a good experience), contributing to the movies The King of Jazz (1929), Lost Horizon (1935), Pennies From Heaven (1936), and Stormy Weather (1943). He even worked for television, writing music for Gunsmoke and Perry Mason.

(Compare the big, green box of today to whenever this shot from L.A.’s Department of City Planning website was taken.)

While Still slowed down in the 1950s, he continued to compose operas, Bayou Legend, A Southern Interlude, and Costaso among them. He also stayed busy accepting sacks full of honorary degrees and awards.

After spending several years in a nursing home, William Grant Still died of a heart attack on December 3, 1978 at the age of 83.

As far as the house is concerned, I don’t think anyone would argue it’s got any architectural significance. Still lived here with Arvey, their son, Duncan Allan, and daughter, Judith Anne. Three years before he died, the Cultural Heritage Board declared his home a city monument because of the contribution made by Still to the culture of Los Angeles and the world.

Sources:

Cariaga, Daniel “Composer William Grant Still Dies” The Los Angeles Times; Dec 6, 1978, p. H29

Arvey, Verna In One Lifetime The University of Arkansas Press 1984 Fayetteville

Smith, Catherine Parsons William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions University of California Press 2000 Berkeley, Los Angeles, London

Up next: Paul R. Williams Residence

Hey, you're not a rube. I knew who Wm. Grant Still was, but I had NO IDEA he wrote film scores! Duh, who's the rube now?

ReplyDeleteThanks, as always, I'm in N.CA, but this is one of my favorite blogs.

Thanks, Donna. I feel less rubish. Give my best to S.F.

ReplyDeleteArchitectural significance? For 1923 you could say it’s fairly…modernistic. Modernistic and…Spanish? Ok, so Gill’s Dodge House with red barrel tile it ain’t.

ReplyDeleteAnd because my mother never taught me the old “if you can’t say something nice” chestnut…I’m kind of mesmerized by the things done to this house. Assuming that the vintage image was taken in 76 when the house was declared, how in heaven did the owners get away with removing the sidelights from the front door? Replacing the wooden double-hungs with aluminum sliders? Enclosing that side door, replacing it with a fan light? And those concrete surrounds around the windows? Are they intended to lend an…Egyptian element to the proceedings? The Still House: Spanish Colonial International-Modern Egyptoid since 1980. (At least the whole viridian green is reversible.)

I mean, the Mills Act was already State Law and then this, as a qualified historical property, was getting an economic incentive to NOT do this sort of thing. If anybody’s a rube here, could it have been the City?

Nathan, you've shamed for calling this a "big, green box." My money's on the city not knowing of changes by an owner who opted to beg for forgiveness rather than ask for permission. I promise to check the Still House file next time I'm at City Hall. In the meantime, I've got $65 for a certain Antonio Villaraigosa to get you on the Cultural Heritage Commission.

ReplyDeleteI'm a rube and I'm o.k. with that (I think since I'm not sure what a rube is).This house must have been recently acquired. I noticed in your flikr page that the instruments of home repair line the drive near the van. Outside of the vinyl window treatments, I think the house is looking spiffy in comparison to it's before picture.

ReplyDeleteI don't recall Nathan's comment being up before I chimed in. Now I'm a super duper rube. So am I to understand that when someone purchases a home that falls under the Mills Act they're given funding for improvements?

ReplyDeleteIs concrete surrounds a facetious way of saying bulky? I'm going to look up Gill's Dodge House. A few years back I was informed by a women working the arts angle of Santa Fe Springs that they discovered a home on the property of Pioneer Park that was a previously unknown Gill. A kind of mish mash.