Monday, November 24, 2008

"West Adams"

We take a break from our regularly scheduled posts (or not so regularly, lately) for a quick plug for West Adams, yet another local history compendium from our favorite South Carolinians, Arcadia Publishing (the company has published more than 4,000 of these books – just scan the Los Angeles-related editions if you need to kill an evening).

Suzanne Tarbell Cooper, Don Lynch, and John G. Kurtz have done a fantastic job assembling West Adams, all about the neighborhood that, “by the end of the 20th century… had become one of the first bedroom communities in fast-growing Los Angeles.” The authors, pictured above, all live in West Adams, and the work they’ve done here covers the gamut from cottages to mansions, from St Vincent de Paul’s to St Paul’s. And there are more than a few Historic-Cultural Monuments highlighted.

(If the L.A. City Nerd were still with us, he could tell us why so many of the HCMs in West Adams are not in the designated planning community of West Adams, but rather South Los Angeles.)

A book signing was held on Saturday, November 22, at the Miner Residence next to Chester Place, thanks to the West Adams Heritage Association. The Miner Residence, named for Randolph Huntington Miner and his wife, Tulita Wilcox Miner, was also home to Theda Bara and Fatty Arbuckle. Joseph Schenk and Norma Talmadge owned the mansion, too. Today the home is the AMAT House.

Congratulations, Suzanne, Don, and John on a job well done.

Buy your copy of West Adams on Amazon here.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

No. 199 - David Familian Chapel of Temple Adat Ariel

David Familian Chapel of Temple Adat Ariel

1949 – Herman Charles Light

5540 Laurel Canyon Boulevard, Valley Village – map

Declared: 9/20/78

This is the first structure built as a synagogue in the San Fernando Valley. It’s also the site of the Valley’s first bat mitzvah. The David Familian Chapel was dedicated by Rabbi Aaron M. Wise on November 7, 1949, but its congregation first congregated nearly a dozen years earlier.

On January 21, 1938, fifteen of the San Fernando Valley’s 100 Jewish families (15/100 = 15%) met in a private home and, to put together religious services and establish a Sunday school for kids and a social club for adults, founded the Valley Jewish Community Center. The congregation met in a variety of places – homes, the American Legion Hall on Magnolia Boulevard, the North Hollywood Women’s Club – before buying a former speakeasy at 12800 Chandler Boulevard around Coldwater Canyon. In 1944, Universal president Nate Blumberg and his wife, Vera, donated to the congregation a two-acre plot at the corner of Burbank and Laurel Canyon Boulevards.

Five years later, Isadore and George Familian donated the $75,000 (the single largest gift to a West Coast synagogue at the time), 350-seat chapel to VJCC in memory of their father, David. David Familian was a Russian immigrant who, after running a junk business here, switched to dealing in plumbing supplies, forming the Familian Pipe and Supply Co. One of Los Angeles’s leading philanthropists, he later bought out Price-Pfister Brass Mfg. Co.

Herman Charles Light designed the synagogue. Alfred Lushing built it, and Mischa Kallis, an art director at Universal, with Rabbi Wise designed the eleven stained-glass windows depicting major Jewish holidays. I wish I could’ve gotten a better picture of them. (I left a phone call there, but never was called back.)

The congregation outgrew the Familian Chapel and by 1968 a new, 1,500-seat sanctuary had been built and dedicated. The Valley’s oldest synagogue continues to be used for services, weddings, lectures, and concerts. Today the Valley Jewish Community Center is known as Adat Ari El (Hebrew for ‘Lion of God Congregation’), and this section of North Hollywood is called Valley Village (Angelino for ‘No, Really, Not North Hollywood’).

Governor Gray Davis proclaimed November 7, 1999, “David Familian Chapel Day”. Two months earlier The David Familian Chapel was made a California State Landmark. Unfortunately, Rabbi Aaron M. Wise, who not only was responsible for VJCC’s national reputation but also championed equal rights for women and marched with Martin Luther King, had died that July.

Sources:

“Familian Chapel Consecrated at Jewish Center” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 9, 1949, p. A3

“Valley Jewish Center Celebrates 25th Year” The Los Angeles Times; Aug 18, 1962, p. B8

“Valley Jewish Center Dedication Scheduled” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 7, 1968, p. O12

Oliver, Myrna “Aaron Wise; Civil Rights Leader, Rabbi of Influential Synagogue” The Los Angeles Times, Jul 8, 1999, A16

Andres, Holly J. “Valley’s Oldest Synagogue; Dignitaries to Gather Sunday at Chapel’s 50th Anniversary” Daily News; Nov 6, 1999, p. N.20

Liu, Caitlin “Jewish Cahpel’s 50th Anniversary Marked” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 8, 1999

McLellan, Dennis “Isadore Familian, 90; Philanthropist” The Record; Jun 16, 2002, p. L.07

Up next: Second Baptist Church Building

Thursday, November 13, 2008

No. 198 - KCET Studios

KCET Studios

1920

4401 Sunset Boulevard – map

Declared: 9/20/78

The ample, red-brick building fronting the south side of the 4300 block of Sunset Drive in Los Feliz holds nearly ninety years of Hollywood history. But while the structure dates back to 1920, the property’s ties with Hollywood filmmaking go back a few years farther, to 1912.

Born in 1851 in present-day Poland, Siegmund “Pops” Lubin emigrated to the United States in 1876. Edison film distributor, theater owner, studio head, and maker of cameras, projectors, and printing machines, Lubin set up his Lubin Manufacturing Company in Philadelphia around the turn of the century. In 1912, Lubin opened a west coast branch on a chunk of land at 1425 Fleming Street (now Hoover). Lubin made just a couple of films here before selling the property to the Essanay Film Company the following year, moving on the East Los Angeles. “Pops” Lubin died near Atlantic City in September 1923.

Essanay, which got its name from the ‘S’ and ‘A’ initials of its founders, George K. Spoor and Broncho Billy Anderson, lasted on Fleming Street for just a couple of months, but long enough to churn out twenty one-reel westerns.

Vacant throughout the summer of 1913, the property saw the Kalem Company move in that October. (Kalem was named for owners George Kleine, Samuel Long, and Frank Marion. Folks back then really liked their initials, apparently.) Kalem made films here into early 1917, going out of business by year’s end.

By the beginning of 1918, theatrical agency Willis & Inglis had moved onto the property, building a couple of stages and setting it up as a rental studio. With that August’s arrival of movie producer Jesse D. Hampton, the lot was soon known as Hampton Studio. Jesse split about five months later, but not before having made more than two dozen films with stars including William Desmond and H.B. Warner.

Willis & Inglis founded Charles Ray Productions with Ray in 1920. (Charles Ray, it turns out, was a pretty big cheese as an actor in the late teens and early twenties. Why didn't I know he was so famous?) It was when Charles Ray Productions took over the property that this good-looking brick building was built. (KCET uses a Sunset Boulevard address, but to get a look at the exterior of the old studio, you need to drive around the block – something I had never done.)

Charles Ray Productions – along with Charles Ray – went bankrupt by 1923 after a string of failures, most notably that year’s The Courtship of Myles Standish. (Although the studio’s reconstruction of the Mayflower became a local tourist attraction, no copies of the film survive.) It was the Bank of Italy (later the Bank of America) which took the lot into receivership and re-addressed the property from 1425 Fleming Street to 4376 Sunset Drive.

The bank returned the lot to its days of the late teens when it became once again a rental studio. It remained rental after former actress Jean Navelle bought the property in 1927. She lost it after the Crash of ’29, and the studio went back into the hands of the Bank of Italy. In 1933, Martha J. Like, the mother of sound engineer and head of International Recording Engineers, Ralph M. Like, bought the lot. This was after Ralph had converted Stage A for sound and just a year after he built what is today’s Stage B of KCET. The lot became home to Like’s Action Pictures and, later, Mayfair Pictures.

W. Ray Johnston’s Monogram Pictures Corporation, a company who’s history stretched back to 1915, bought the lot from Like in 1943, having rented the studio for years (they had been based at the former Tiffany Studios nearby at 4516 Sunset). While under the Monogram moniker, the studio produced tons of movies, mostly in the ‘B’ and ‘C’ categories. Charlie Chans, Joe Palookas, Bowery Boys, and Cisco Kids were produced here, along with those Jiggs & Maggie and Bomba, the Jungle Boy, films. And don’t forget all those western: Jimmy Wakely; Whip Wilson; and more than sixty Johnny Mack Brown westerns.

In 1946, Allied Artists was formed as a subsidiary company to Monogram. While Allied was created to concentrate on bigger budgeted films, I know them mainly for such movies as Invasion of the Body Snatchers and Attack of the Fifty-Foot Woman (but Love in the Afternoon and Friendly Persuasion were theirs, too). Allied retired the Monogram name in 1953.

So are the bars over the brick wall left over from when there was a door there, or are they there to protect the air conditioner?

Allied Artists gave up producing for distributing and fled to New York City in 1964. The property became a rental lot once again. ColorVision bought “Pops” Lubin’s old property in 1967 but went bankrupt two years later. In the summer of 1970, the L.A. Times announced public television station KCET was buying the 3.5 acre lot for $800,000. Community Television of Southern California the station’s parent company, finalized its purchase of the property in 1971. KCET relocated from its original home at 1313 North Vine Street in October 1971. The new $3.2 million studio was dedicated November 18, 1971.

One last note about the studio: in 1979, an employee’s errant karate kick exposed behind a damaged wall an ornate screening room dating to the Charles Ray days. It’s now being used as a meeting room.

I lifted maybe 79% of the information in this post from KCET’s history page on its website. Go to it for a lot of lot history along with photos of the property through the years. I emailed them to find out who assembled the article so I could give him or her an extra thanks, but I didn’t hear back. (Update: As I expected, the piece was written by Marc Wanamaker. Thanks, Marc.)

The Vista Theater close by.

Oh. And when you swing by HCM No. 198, make sure you visit the old Vista Theater at 4473 Sunset Drive nearby. Designed by Lewis A. Smith, it opened as Bard’s Hollywood Theater in October 1923 on the site of the filming of D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance.

Sources:

Knapp, Dan “Allied Artists Studio Purchased by KCET” The Los Angeles Times; Jul 27, 1970, p. D14

“Koch, Sharon Ray “Fete Hails New Home of KCET” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 17, 1970, p. G1

“$3.2 Million Studio Dedicated by KCET-TV” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 19, 19171, p. A26

Turpin, Dick “KCET Will Build Administrative Plant” The Los Angeles Times; Aug 10, 1975, p. D1

Kaplan, Sam “Remnant of Old Hollywood” The Los Angeles Times; May 6, 1979, p. K1

Up next: David Familian Chapel of Temple Adat Ariel

Monday, November 10, 2008

No. 197 - Britt Mansion and Formal Gardens

Britt Mansion and Formal Gardens

1910 – A.F. Rosenheim

2141 West Adams Boulevard – map

Declared: 8/23/78

Man, it’s encounters like the one in which I took part at Monument No. 197, the Britt Mansion, that force me to seriously consider taking up a less confrontational hobby, like roller derby or crocodile wrestling. I kid about the wrestling, but seriously, visiting the Britt Mansion has put me in a lousy mood.

Of course, coming up on my 200th monument, I’ve learned how taking pictures indoors at landmarks generally leads to famine and plague, so I was fully expecting to being stopped from taking any interior shots of the Britt Mansion, which I was. I balked when a guard stopped me from photographing the designation plaque on the outside of the building, but I was on their property, so whatever. But when a security guard came out to the curb and told me no photography of the landmark was allowed, even from the sidewalk – it’s okay from across the street, I learned – well, then I started to argue my rights. He goes insides, returns with another worker, and the two of them look so fretful, like I’m about to torch the place. So, you know what? I figured I got a couple of shots, so I split. Who wants to deal with that? Not me. But, again, it really demotivated your sensitive blogger.

But on to the landmark.

The Los Angeles Times announced at summer’s start in 1910 that A.F. Rosenheim was finishing plans for a fifteen-room residence at the corner of West Adams and Grammercy Place. The 55' x 75' structure would be brick, with a granite base and slate roof. Eugene W. Britt, one of the city’s more prominent lawyers, was doing the commissioning.

Britt was born on Christmas Day, 1855, in Harrisonville, Missouri. Admitted to the bar in 1878, Britt moved to California, up in Lake County, that same year. He formed a law firm with William J. Hunsaker in San Diego in 1887. (The Queen Anne home Britt built that year stands today as San Diego’s landmark Britt Scripps Inn.) The partnership lasted until 1892 when Hunsaker moved to Los Angeles. Britt served on the California Supreme Court Commission starting in 1895, but he resigned when, in 1900, he relocated to L.A. and rejoined Hunsaker. (Hunsaker & Britt eventually became Hunsaker, Britt & Cosgrove with the addition of Terence Cosgrove.)

Eugene Britt was also the president of the Los Angeles Bar Association in 1912 and served as delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1916.

At the end of the oughts, Britt hired Alfred F. Rosenheim to build for him a mansion out in what was known as Arlington Heights. The land had once been part of the Mexican land grant Rancho Las Cienegas. Awarded to Juanario Avila in 1823, the land was divided among thirteen claimants in 1866 by the L.A. District Court. The chunk which became Arlington Heights was first of the parcels of land to be subdivided. That was in 1887.

Construction of the Britt Mansion was begun in mid-October 1910. At this time it was estimated the Georgian home would run to $50,000. The little I saw of the Beaux Arts interior had me see why the Times called the mansion “one of the handsomest” on the “fashionable thorough-fare” of West Adams. Dark oak floors, lots of wood paneling, and heavy beamed ceilings were pretty much all I could get a look at. I sure didn’t see the alcove, originally Britt’s music room with a ten-inch platform for a performing stage (Britt had it removed after just two years), or the old dining room paneled in Tabasco mahogany.

At some point, the home was bought by Abram and his wife, whose name was something like De Etta. Their last name was maybe Detwiler, but it could’ve been Henderson for all I can read my damn pathetic handwriting. (The sale had happened long before Britt died as St Vincent’s Hospital in February 1935. Although he was living at the Chapman Park Hotel at the time of his death, he had been residing with his wife, the former Harriet Biggerstaff, at 532 South Arden Boulevard, when she passed away in January 1934. Hunsaker died in his home at 515 South Harvard Boulevard on January 1933.)

Oh, so get this. The home was designated an official city landmark in the summer of 1978, right? Well, two years later, the owner, Gladys Snyder, realizes that because of the landmark status she’s having trouble selling the home to developers who were champing at the bit to put up an apartment building on the site. Claiming the city designated the home without her knowledge, and that the home could be neither sold nor repaired, Gladys demanded the city undeclare the Britt Mansion, which it did in a 12-1 vote in September 1980, paving the way for the home’s demolition. Good news for Gladys, who accused the Cultural Heritage Board of “Gestapho [sic] like tactics”, and complained, “as long as the house is designated a historic cultural monument, I shall be a prisoner in a decaying, rotting, unsafe structure.”

Rather than face the wrecking ball, the Britt Mansion was purchased by First Interstate Bank in 1982 at the urging of Peter and Ginny Ueberroth who had recently begun privately supporting a giant collection of sports memorabilia started by Paul Helms back in 1936. The Britt Mansion became the collection’s fourth home, opening its doors as a museum in 1984 after a $2 million renovation. Ueberroth and First Interstate donated the Helms collection and property to the Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles the following year. The organization, now with a research library, today is called the LA84 Foundation.

You know, I could not find whether or not there was ever any official re-designation of the Britt Mansion. Like I said, though, there is an HCM plaque placed on the landmark’s exterior. Which is off-limits for photographers, I repeat. Maybe the Foundation doesn’t want to risk photos being taken of the scientific testing on live, semi-conscious kittens and puppies taking place on the grounds (or so I’ve heard).

The Britt Mansion was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Sources:

“Plans Colonial House.” The Los Angeles Times; Jun 26, 1910, p. VI6

“New Show Place for West Adams” The Los Angeles Times; Oct 30, 1910, p. VI1

“W.J. Hunsaker, Attorney, Dies” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 14, 1933, p. A1

“Lawyer’s Wife Dies of Illness” The Los Angeles Times; Jany 27, 1934, p. A6

“E.W. Britt Succumbs” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 16, 1935, p. A1

“Britt House Loses Its Status as Monument” The Los Angeles Times; Sep 14, 1980, p. J12

Hiserman, Mike “Museum Showcases 50,000 Items of Memorabilia” The Los Angeles Times; Jul 26, 1984, p. LB7

Up next: KCET Studios

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

No. 196 - Variety Arts Center Building

Variety Arts Center Building

1924 – Allison & Allison

940 South Figueroa Street – map

Declared: 8/9/78

This poor building. Just a year or so ago, it was probably all jazzed to become an integral part of South Park’s revitalized entertainment area, what with all the Nokias and this-and-that Live (does anyone else find these names confusing?). But now, it’s kind of loitering, vacant, feeling gypped, watching the parade pass by, seeing its neighboring lots get all the love, and humiliatingly trying to rent itself out for location shoots. Hardly fair, considering its eighty-four-year history.

I know the building was finished in 1924, but let’s jump back to the era of the Reconstruction to get this history rolling.

A contemporary of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, suffragist and abolitionist Caroline Severance moved with her family to Los Angeles in 1875 (click here to see a picture of their estate, El Nido, at 806 West Adams Boulevard – or the trees and shrubs there, anyway; it was demolished in the early 1950s). By the time she arrived in Our Fair City, Severance had already compiled an impressive resume, having co-founded in 1868 the first women’s club in the United States, a Boston organization called the New England Woman’s Club. The next year, she co-founded the American Woman Suffrage Association. No sooner had she landed in L.A. she started California’s – and one on the country’s – first kindergartens, at First and Hill Streets. She and her husband, Theodoric, founded the city’s first Unitarian congregation, Unity Church. At the age of 91, she became the first woman to vote in California (this last item reeks of apocryphality, if you ask me). In 1891, Severance founded the Friday Morning Club, L.A.’s first women’s political club, with eighty-seven members (its membership eventually peaked at 3,800).

The Friday Morning Club soon formed a corporation which, with money made from issuing stock, bought a chunk of land on Figueroa between Ninth and Tenth for a clubhouse it would in turn lease back to the club. This was in 1899, after holding its meetings for the last five years in space in the Owens Block downtown.

The gals laid the cornerstone of the club’s new $13,000, two-story Mission-style headquarters on September 14, 1899, and took possession of the building four months later, on January 19, 1900. An opening reception was held four days after that.

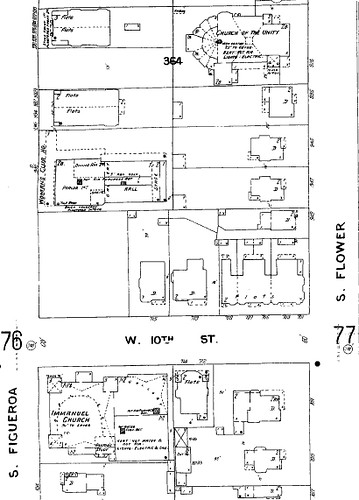

Below are four images: a head-shot of Caroline Severance; ground-breaking of the first Friday Morning Club clubhouse (watch out for those troublemakers on the roof!); said clubhouse (pretty sweet, no?); and a piece of a 1906 Sanborn map showing its location at 940 South Figueroa (I don’t know it that Church of Unity shown is home to the Unitarian Church started up by Caroline and Theodric years earlier).

In April 1922, the Friday Morning Club announced preliminary plans by brothers in architecture, James & David Allison (whom we’ve already met here and here), for a brand new, five-story, Italian Renaissance clubhouse had been submitted and were approved. The first floor would contain the club’s executive offices, the second would hold lounges and a library, the third would house the auditorium, the fourth would contain the assembly room and a dining room for 500 people, and the fifth would be devoted to an art gallery and two small clubrooms. (At this time, the cost was estimated at about $400,000; ten months later, officials were saying the new building’s pricetag had ballooned to between $750,000 to $800,000.) The bad news is the new headquarters would replace the 1900 building, and demolition on the latter began almost immediately.

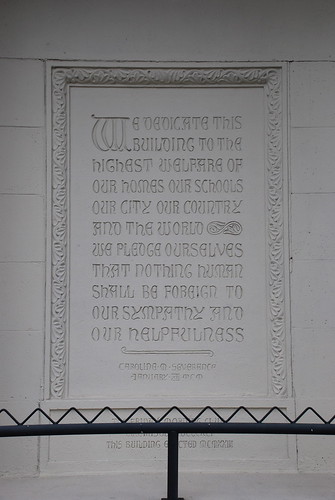

Next to the front entrance, you’ll find a memorial tablet dedicated to Caroline Severance. The words, taken from a speech given by Severance on her 71st birthday, had earlier been carved in bronze and were placed on the old clubhouse. Unveiled on January 12, 1923, on what would’ve been Severance’s 103rd birthday (she died at the age of 94 in 1914), the new tablet was later incorporated into the current building’s façade.

You can read the Friday Morning Club’s motto carved into the Figueroa Street front: “In essentials unity – in nonessentials liberty – and in all things charity”.

Housewarming for the new Friday Morning Club headquarters was planned for April 16, 1924, with the clubhouse’s first speaker, Rebecca West, scheduled for April 18.

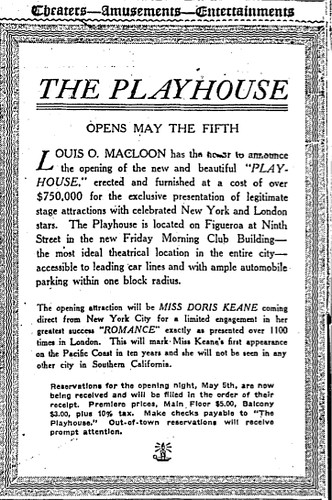

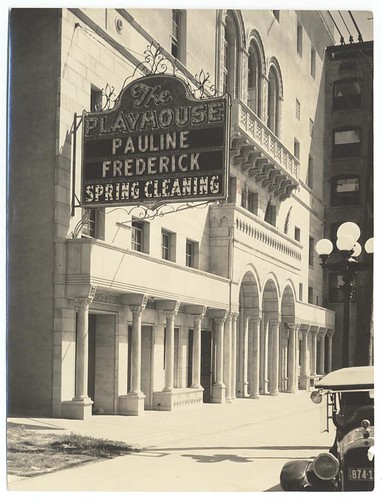

From the get-go, the 1,200–seat auditorium was busy. Leased as The Playhouse, with the husband and wife team of Louis O. Macloon and Lillian Albertson producing, the theater’s first performance was on May 5, with Doris Keane starring in Romance. Albertson directed the show, and Will Rogers emceed.

The Playhouse – sometimes referred to as the Figueroa Playhouse – became a major stop on the vaudeville circuit. Clearly not an ornate palace like the theaters on Broadway, the serviceable Playhouse was said to sport great acoustics. The day’s top stars, from Laurel & Hardy to Lionel Barrymore, trod the boards here. Clark Gable made his acting debut at the Playhouse in May 1925 in Romeo and Juliet.

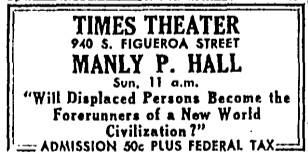

CBS Radio Playhouse broadcast The Burns and Allen Show from the theater from 1932 to 1938. By 1940, the Playhouse was out and the Times Theater was in. Live shows continued, but you could also catch movies here, too.

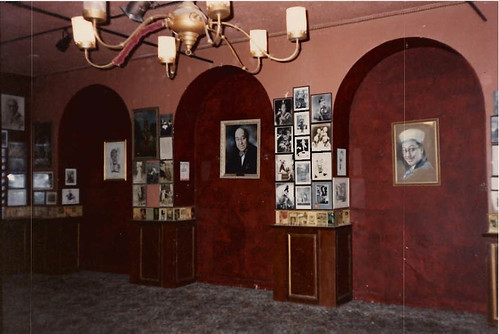

The Friday Morning Club sold the building to Milt Larsen’s non-profit Society for the Preservation for Variety Arts (in 1984, an annual membership to the organization would set you back $90). Besides offering live performances in the vaudeville tradition, Larsen, the owner of Hollywood’s Magic Castle, also set up a small museum dedicated to the artform. Luckily, Larsen’s 1982 plan to take apart the theater – now known as the Variety Arts Center – and reassemble it into a slick, modern shell that would’ve encompassed the entire block never materialized.

J. Eric Lynxwiler says the Center's neon signs out front are “the only re-arrangeable neon letters left in the city.” Had I know that, I would've stolen them.

In 1984, the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency lent Larsen’s Society half a million bucks to seed a multi-million dollar rehabilitation for sixty-year-old building. Things looked promising, but that Thanksgiving the CRA was forced to scramble to come up with a $1.7 million bail-out package to block an IRS auction of the landmark (seems someone owed $130,000 in back taxes). Larsen was forced to close the Variety Arts Center on New Year’s Eve, 1988.

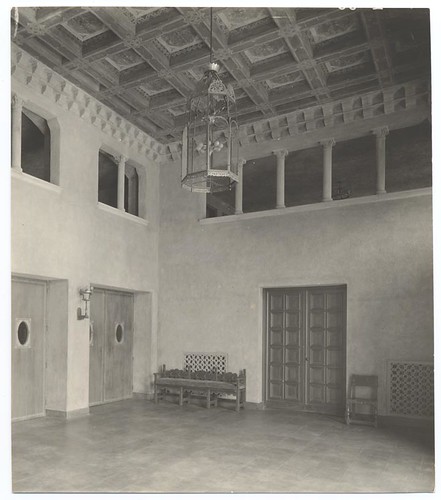

Now, while I didn’t get inside the Variety Arts Center, Rita in the Office of Historic Resources was a hero in providing these twenty-year-old photos of the building’s interior. Thanks, Rita!

J.S. Sehdeva was running the landmark as a club by the early 1990s. Snoop Dogg and Dr Dre’s film, Murder Was the Case, premiered here on November 3, 1994. And here’s a link to the Butthole Surfers’ gig here on November 7, 1987 (and, if you squint your ears real hard, you can hear Doris Keane spinning in her grave).

AEG – the Anschutz Entertainment Group, in case you didn’t know – purchased the Variety Arts Center for around $8 million in 2004, with the intention of developing it as part of the L.A. Live area a few blocks to the south. Guess what never happened.

In late 2006, David Houk, former owner of the Pasadena Playhouse, bought the building from AEG for an undisclosed amount. However, Houk, whose Houk Development Company is also (not) working on the Park Fifth high-rise project, is now looking for a buyer or a partner of the Variety Arts Center.

I hope – and suspect – there’s a good amount of life left in the old Playhouse. I enjoy real well the thought of the landmark again becoming a home to some sort of alternative theater, especially in the context of an area that’s becoming increasingly super-slick and corporately branded (although I sure do like the Figueroa Hotel directly opposite).

The non-original photos here are from all the usual sources: the L.A. Public Library, the CA State Library, and USC’s Digital Archive.

Sources:

“Women’s Clubhouse.” The Los Angeles Times; Sep 11, 1899, p. 10

“Corner-stone Laid.” The Los Angeles Times; Sep 15, 1899, p. 14

“Clubs of Women.” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 20, 1900, p. I12

“Building Plan Completed” The Los Angeles Times; Apr 9, 1922, p. V1

Nye, Myra “Founder of Club Honored” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 13, 1923, p. II1

“Excavating Gives Club Merriment” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 13, 1924, p. 26

“Clubs of Women.” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 24, 1900, p. I5

“Clubhouse Gets Last Work Soon” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 3, 1924, p. 25

“Dues Increase Finishes Work” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 10, 1924, p. 26

“Introducing Doris Keane” The Los Angeles Times; May 4, 1924, p. B21

Drake, Sylvia “New Look for Variety Arts Center” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 21, 1982, p. I1

Drake, Sylvia, “Stage Watch” The Los Angeles Times; Apr 26, 1984, p. K2

Connell, Rich “Historic Arts Center Spared From the IRS Auction Block" The Los Angeles Times; Nov 27, 1984

Rasmussen, Cecilia “L.A.’s Leading, Now Forgotten, Suffragette” The Los Angeles Times, Jun 7, 1998, p. 3

Vincent, Roger “Revival Falters for Variety Arts Center in Downtown Los Angeles” The Los Angeles Times; Oct 4, 2008

Bret, David Clark Gable: Tormented Star, Carroll & Graf, 2007, New York

Up next: Britt Mansion and Formal Gardens