Villa Maria

1908 – F.L. Roehrig

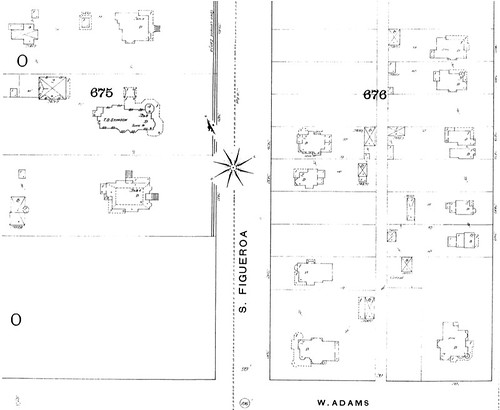

2425 South Western Avenue – map

Declared: 6/12/80

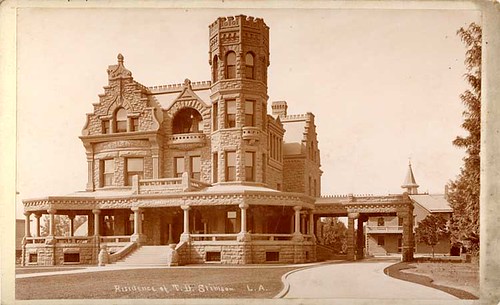

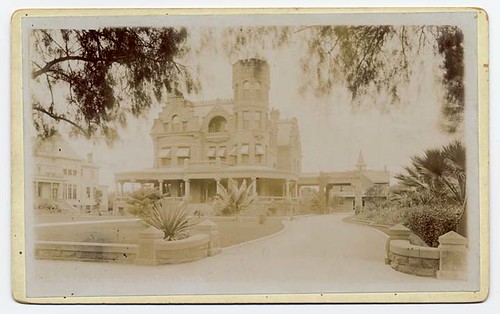

William Edmund Ramsay, born the son of Scottish immigrants in Quebec in 1855, made his fortune in the lumber business in Saginaw, Michigan, and Lake Charles, Louisiana. In 1906, Ramsay moved to Los Angeles with his family and bought up three parcels of land between Western Avenue and Adams Place (the latter renamed St Andrews Place in 1914) in West Adams Heights. Included in the mix were more than two and a half acres Ramsay purchased from Mira Hershey. Ramsay then hired architect Frederick L. Roehrig (1857 – 1948) to design this 9,000 square foot, forty-room mansion. Completed in the summer of 1908, the estate wouldn’t remain Ramsay’s home for long, as he died of “heart trouble” in early February the next year.

In that summer of ‘08, the L.A. Times wrote of Ramsay’s 225 x 500 foot property, “Probably no more entertaining spot could be found in all Los Angeles on which to build a handsome home.” Roehrig and the building contractors, the Barber-Bradley Construction Co., created for the Ramsays a three-story, Tudor Revival masterpiece made of stone and half timber, plaster finish, and topped with a slate roof.

See! The grand entrance hall, ceiling-beamed and wainscoted in mahogany.

Behold! The former living room/library. Originally, the room sported electric fixtures made of brass with Tiffany shades. Like with the rest of the first floor, this section of the home featured leaded windows.

Witness! The very splendid dining room, also in mahogany.

Observe! The kitchen.

View! Other pictures.

Art glass, from the inside and out.

The second floor contained five bedrooms, each finished in white enamel and given its own bathroom. The showcase of the Ramsay’s third floor was a 25 x 90 foot assembly hall/ballroom. That floor also had four bedrooms as part of its servants’ quarters.

Going back outside, F.L. Roehrig was also in charge of the estate’s landscaping. Here’s the old pergola, sans the original lily pond.

On the lot’s northwest corner stands the two-and-half-story carriage house with chauffeur’s quarters.

The home originally did have a tennis court, but probably not a basketball court.

Back in 2001, historian Cecilia Rasmussen wrote the Ramsay estate – after William’s death – became the site of “lavish parties, quarrels, a shooting and a suicide – of which no details survive.” (Rasmussen claims scenes from a Charlie Chaplin film were shot on the lawn – anyone have any idea which movie?) Ramsay’s widow, Katherine, by the way, passed away in July 1916.

Owners #2. William Durfee and Nellie McGaughey were each thirty-two-years old when they met; she was a filthy rich society dame, Durfee was “her mother’s horse trainer, a harness racing driver, a gambler, married and the father of two.” Soon after Nellie’s mom died in 1911, the couple wed, living in the South Figueroa Street mansion that had been the home of Nellie’s mother and her husband, banker Nicola Bonfilio. In 1924, a year after Bonfilio’s death, the Durfees bought the Ramsay estate for $105,000.

The north (top) and west facades.

Unfortunately, William Durfee died three years later after eating some poisoned fish on a trip to the Columbia River. Nellie didn’t take Durfee’s demise all that well, giving a go at suicide on a few occasions. While none of those attempts was successful, the poor woman grew to be an eccentric kook who, among other things, preserved her home in a museum-like fashion as kind of a shrine to her late husband – you know, keeping his clothes in his closet, his booze in the wine cellar, and the key to his bedroom around her neck. This lasted until she finally passed away in February 1976, a few months short of turning 100.

Owners #3. In the spring of 1978, the Brothers of St John of God, who, in the 1960s, demolished a turn-of-the-century mansion next door to the Ramsay-Durfee estate to make room for their nursing hospital, bought the seventy-year-old mansion for $470,000. The Brothers auctioned off much of the original furniture, fixtures, and Nellie’s seventy oriental rugs.

I should point out the Brothers have apparently been excellent stewards of the property. It was during their ownership the mansion was declared a Historic-Cultural Landmark as Villa Maria, and they were gracious to open up the house as part of a neighborhood tour put on by the West Adams Heritage Association last June. That’s when these pictures were taken.

The way in and out toward Western Avenue.

In addition to the aforementioned, unidentified Chaplin film, the Villa Maria has been the location for a few movies, including True Confessions and Sister Act II: Back in the Habit.

Sources:

“English Domestic Architecture Employed in Designing Handsome West Adams Heights Home.” The Los Angeles Times; Sep 27 1908, p. V1

“Catholic Order Purchases Historic Durfee Mansion for Headquarters” The Los Angeles Times; Mar 12, 1978, p. I25

Rasmussen, Cecilia “West Adams Mansion: If Only These Walls Could Talk” The Los Angeles Times; Jul 8, 2001, p. B3

Up next: El Greco Apartments

continue reading...