Glendale-Hyperion Bridge

1928 – Merrill Butler

From Ettrick Street to Glenfeliz Boulevard – map

Declared: 10/20/76

Man, this Glendale-Hyperion Bridge is huge and not a little complex. In fact, the whole thing is treated as six different structures: there are two chunks of Hyperion Avenue bridge, spanning Riverside and the I-5; in between, the viaduct portion over the L.A. River; don’t forget the two Glendale Boulevard sections – north and south, each twenty-eight-feet wide and about 400 feet in length; finally, included in the group is the Waverly Drive Bridge, crossing over Hyperion near the landmark’s western edge.

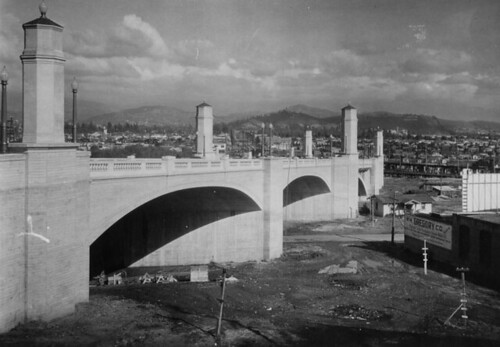

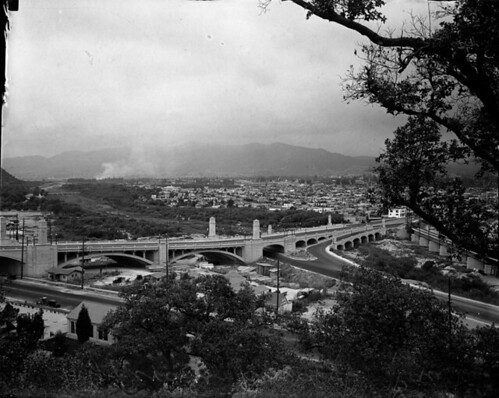

Top shot taken from Waverly Drive Bridge, bottom shot from the city's Dept of City Planning website.

Merrill Butler, Engineer of Bridges and Structures for the city’s Bureau of Engineering from 1923 to 1961, gets the credit as designer of the monument. The total length of the main portion is close to 1,400 feet. Crews used more than 35,000 cubic yards of concrete and 6,000,000 pounds of reinforcing steel in the total construction. They also drove about 1500 wooden and 3200 concrete piles to support the piers and abutments. There are thirteen arches: two are 135-feet each; eight are forty-eight feet; one is sixty-eight feet; and two stretch 118-feet.

Top picture is the bridge over Riverside Drive, the lower is courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Archive.

The Board of Public Works received construction bids on March 31, 1927 for the project, building a new bridge to replace an old wooden trestle. By May 18, the only contract outstanding was “the one for the separation of the grade structure between Glendale avenue [sic] and Riverside Drive.” I’ve seen several different financial figures attributed to this bridge, but, that spring, the total project cost was pegged at close to $2 million, with the county chipping in $660,000 and the Pacific Electric Railway and the city dividing the rest. Construction began May 27, 1927.

Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Archive. Dated December 4, 1928.

Speaking of the P.E., the Glendale-Burbank line ran over the L.A. River just south of the bridge. Go to Tom Wetzel’s page here and scroll down to see a fantastic color shot of the Red Cars crossing the river. The tracks are long gone, but the old cement piers still stand:

That October, the L.A. Times was reporting officials were still promising the span would be finished no later than May 28, 1928, the date originally planned for completion. That date wasn’t chosen at random, I’m guessing. The bridge was scheduled to be a memorial to those who died fighting in World War I, and 5/28/28 was Memorial – or Decoration – Day. The bridge, though, wouldn’t be near ready by then.

As construction dragged on, opening day was pushed off time and time again. For a while, it looked as though it’d be ready for traffic by Armistice Day, November 11, 1928. However, it wasn’t until the end of February 1929 when the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge was completely completed.

On May 30, 1930, four days after Decoration – or Memorial – Day, the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge finally got its official dedication with hundreds of folks turning out for the to-do. Harry A. Towers of the American Legion dedicated the future monument “to the memory of the heroes of the World War who paid to their country the last full measure of devotion.” The Firemen’s Band and Mrs John Wise, soprano, belted out a few tunes. Among the speakers on hand with the designer Butler was Hugh McGuire, the president of the Board of Public Works. Here’s a bleak picture of the memorial, on the viaduct’s south side, just west of the river:

On Riverside Drive.

Just north of the viaduct is one of the few pedestrian bridges to cross the L.A. River. This one is the Sunnynook Footbridge. I had to cross not once, but twice. My crossings were the two least pleasant experiences I’ve had since starting this blog. Here’s a picture of the footbridge, with a photo taken from said structure below it:

Speaking of footbridges, there’s one that spans the 5 freeway, too. You’d think it would’ve been as disconcerting crossing this as the Sunnynook, but it wasn’t to me. This shot was taken from there above the traffic (obviously):

Looking west from the Atwater side.

On June 9, 1928, Mr Harry Sperl, a SoCal distributor of Gardner cars, was the first person to drive over a section of the bridge. “Not even a truck had set wheels on the first unit of the new span,” trumpeted the L.A. Times. He was accompanied by A.M. Troxsan, superintendent of the bridge construction, in a Trojan roadster. In September, though, MGM starlet Dolores Brinkman nabbed the credit as the first person to drive across the whole span. She drove a Packard Eight Phaeton, for those of you keeping notes. Both of these incidents reek as the work of savvy p.r. men, and I wouldn’t bet Harry and Dol truly deserve these honors. Scope Ms Brinkman’s gams here.

The black and white shot, above, from the USC Digital Archive, is interesting for a couple of reasons. First, most obviously, it's pre-5. The freeway would go on to plow under one of the bigger arches shown, the one on the right. Also, you can see the Pacific Electric bridge at the far right.

Today, the bridge is targeted for a whole bunch of improvements including widening and replacing walkways, on-ramps, off-ramps, and the bridge itself, adding railings, dropping in a center median, and lots of seismic improvements. I’m glad to see there’s talk of adding a pedestrian crossing over Glendale Boulevard north, just east of the river. I am, however, disappointed there’s no mention of removing the human poo on the steps leading from the viaduct down to the riverside (no, there’s no picture).

Sources:

“Bridge Will Link Cities” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 28, 1927 p. A1

“Contracts for Bridge Work Given” The Los Angeles Times; May 19, 1927, p. A5

“Work Rushed on Bridge” The Los Angeles Times; Oct 9, 1927, p. E7

“Glendale-Hyperion Viaduct Rapidly Progressing” The Los Angeles Times; Jun 10, 1928, p. G12

“Glendale-Hyperion Span Complete in November” The Los Angeles Times; Aug 26, 1928, p. H6

“First Car Crosses Span” The Los Angeles Times; Sep 30, 1930, p. G9

“Bridge Traffic To Be Speeded” “Glendale-Hyperion Span Complete in November” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 4, 1928, p. E5

“Bridge To Be Open By New Year” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 19, 1928, p. A18

“Hundreds at Viaduct Ceremony” The Los Angeles Times; May 31, 1930, p. A1

Up next: Fire Station No. 27

continue reading...