Griffith Observatory

1935 – John C. Austin and Frederic M. Ashley

2800 East Observatory Road, Griffith Park – map

Declared: 11/17/76

The notion of building an observatory in Griffith Park goes way back to 1903, at least. That’s when Colonel James W. Eddy – the same man responsible for Angels Flight – obtained the rights to build a similar funicular railway in the park. It was his plan to have the tracks lead to an observatory at the peak of Mt Hollywood. That didn’t happen, of course.

In December 1912, Colonel Griffith J. Griffith, the same man who, at Christmastime in 1896, donated 3,015 acres of land for his namesaked park, pledged $100,000 for an observatory – again, atop Mt Hollywood, the park’s highest peak. The Colonel’s record of philanthropy notwithstanding, and despite his well-documented inspiration when visiting the observatory at Mt Wilson, many saw the offer as an act of redemption for the whole “shooting-his-wife-in-the-eye-incident” in 1903 (she lived, and G.J.G went to prison for a couple of years). Griffith was truly jazzed about the project, though, planning the observatory with a Hall of Science, rooftop promenade, movie theater, and solar telescope. The problem, though, was city council said ‘no thanks’ to the Colonel’s offer. They city even briefly reconsidered Col. Eddy’s decade-old plans for a much larger observatory.

The three domes are pure copper.

Colonel Griffith died in 1919, never getting to see his hopes for a park observatory fulfilled. He did, though, will funds for the building of both the Observatory and the Greek Theatre. Legal problems with the will ensued, of course, and, by 1930, the Greek was complete, but the Griffith Trust had yet to break ground on the observatory.

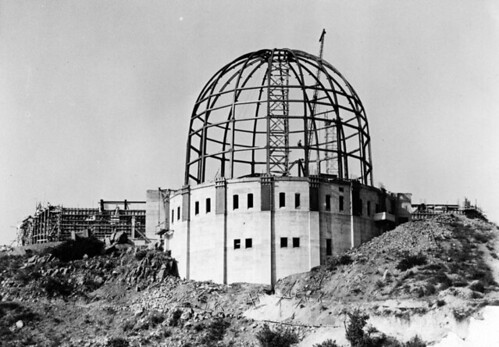

When planning began in earnest (by which time Griffith’s bequest had grown to $750,000), the Trust brought in Caltech physicist Edward Kurth to draw up preliminary plans with the help of Russell W. Porter. In May of 1931, the Griffith Trust and L.A. Park Commissioners chose architects John C. Austin and Frederic M. Ashley to oversee the final plans for the new observatory building. Austin and Ashley hired Kurth to direct the project with Porter as consultant.

The top picture from the L.A. Public Library. In the bottom shot, look how many people came to watch me take pictures.

Further planning included updating Griffith’s idea of a movie theater to a planetarium and buying a twelve-inch refracting German Zeiss telescope ($14,900) along with another pair of telescopes, one of which was a three-in-one solar device.

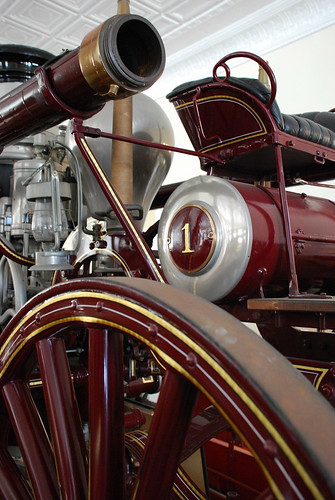

A glimpse of the Triple Beam Coelostat which reflects sunlight to the solar telescopes.

Griffith’s original vision placed the observatory on the peak of Mt Hollywood, but it became apparent that the cost of that location – as well as its accompanying logistic and safety problems – would prove that vision unfeasible. Officials wisely moved the site of the observatory from the top of Mt Hollywood to the hill’s southern slope. Once that decision was made, architect Austin finished his plans within six weeks.

Lower picture: knife fight!

Ground-breaking ceremonies were held on June 20, 1933, with Mayor John C. Porter getting dibs on the first spadeful. Construction began on October 7.

About half a year before the Observatory opened, on November 25, 1934, officials dedicated the forty-foot Astronomers’ Monument on the lawn in front of the unfinished building. A couple thousand people, including Mayor Frank L. Shaw and Governor Frank Merriam, showed up for the ceremonies. The monument was a WPA project conceived by Arnold Foerster and executed by Foerster and five other artists. It features Hipparchus, Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, and Herschel.

The Astronomers' Monument

At a total cost $655,000 (cheap!), the Observatory formally opened on May 14, 1935 with a special reception for a crowd of about 500. The building was officially presented to Mayor Shaw, the city of L.A., and the Department of Parks (now known as the Department of Recreation and Parks) by Bruce H. Grigsby on behalf of the Griffith Trust. The next day, the doors were thrown open to the hoi polloi. Dr Dinsmore Alter was the observatory’s first director, holding down the job until 1958.

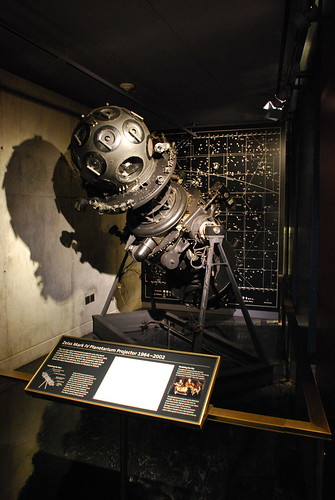

The planetarium – the country’s third – was a big hit, what with it’s 75-foot diameter ceiling and all. The planetarium’s original projector was used until 1964 when it was replaced by the one below (which saw service until 2002). The one below – a one-ton opto-mechanical projector – used a pair of thousand-watt lamps to project 8,900 stars as well as the planets, Sun, and Moon. Today, the 300-seat theater is the Samuel Oschin Planetarium.

Top: Zeiss Mark IV Planetarium Projector (1964-2002); Middle: the planetarium; Bottom: the rotunda

Inside the main entrance is the W.M. Keck Memorial Foundation Central Rotunda, decorated with the works of movie director/art director/1932 Olympics-medallion-designer Hugo Ballin. Ballin, also responsible for murals at the Wilshire Boulevard Temple, Burbank City Hall, and the Title Guarantee Building, was given an $8,000 commission to create eight 11x16 foot panels plus the ceiling’s painting, thirty-six feet in diameter. The octet of murals represents the sciences. The ceiling art features the Zodiac and stars Atlas along with the Roman gods who got planets named after them.

Hugo Ballin's ceiling painting, the "Time" and "Mathematics and Physics" Murals

Hanging from the center of the rotunda is the Foucault Pendulum, a 240-pound ball at the end of a forty-foot steel wire. The ball moves in the same direction, it’s the earth that’s rotating under it. It takes forty-two hours for the pendulum to appear to make a full rotation (but it’s actually the planet that’s doing the moving, remember, thanks to the Coriolis force).

The Foucault Pendulum

By 2002, with about two million visitors annually, the Griffith Observatory shut its doors for what turned out to be a nearly four-year, $93 million restoration/renovation. Rather than spread out or up, the project’s architects, Stephen Johnson of Pfeiffer Partners and Brenda Levin, decided to dig down. 30,000 cubic yards of earth were removed to give the Observatory nearly 40,000 more square feet to play with. Included in the new, lower level are the Leonard Nimoy Event Horizon Theater and the Gunther Depths of Space Exhibit (below). The Griffith Observatory re-opened on November 3, 2006.

One last note. Just two months before the grand re-opening of the Griffith Observatory, Kenneth Kendall passed away at the age of 84. He was the native Angeleno who created the bronze bust of James Dean at the actor’s request back in 1955. Kendall held onto the sculpture for thirty-three years, but, in 1988, donated it to the Observatory, where a pair of Rebel without a Cause scenes were filmed (here's one). The monument was unveiled on November 1.

Sources:

“Planetarium Work Starts” The Los Angeles Times; Jun 21, 1933, p. A1

“Statue and Pool Plan Approved” The Los Angeles Times; Mar 2, 1934, p. A2

“Park Statue Given Public” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 26, 1934, p. A3

“The Griffith Observatory” The Los Angeles Times; May 14, 1935, p. A4

“Park Gift Dedicated” The Los Angeles Times; May 15, 1935, p. A1

Harvey, Steve “People and Events” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 2, 1988, p. 2

Newton, Jim “Los Angeles’ Hillside is Shining Again” The Los Angeles Times; Oct 29, 2006 p. B1

Hawthorne, Christopher Architecture Review; An Icon’s Hidden Virtues” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 2, 2006, p. A1

Reynolds, Christopher “Griffith Observatory Guide” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 2, 2006, p. E28

McLellan, Dennis “Artist Helped Preserve James Dean’s Memory” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 3, 2006, p. B11

Haithman, Diane “An Out-of-This-World Feeling” The Los Angeles Times; Nov 4, 2006, p. B3

The Story of Griffith Observatory and Planetarium, Los Angeles, California, Board of Recreation and Parks Commissioners, City of Los Angeles

Eberts, Mike Griffith Park: A Centennial History The Historical Society of Southern California

1996 Los Angeles, California

Up next: Residence of William Grant Still

continue reading...