Manzanar

1942 - 1945

Highway 395, Inyo County – map

Declared: 9/15/76

The United States operated ten concentration camps to hold Japanese-Americans during World War II. The Manzanar War Relocation Center, located in the Owens Valley about 220 miles north of Los Angeles, was not the biggest but it was the first, admitting the initial eighty-two of its more than 11,000 prisoners on March 21, 1942. Ninety-two percent of Manzanar detainees came from the county of Los Angeles; seventy-six percent from the city proper.

Above: the original military sentry post and internal police post, built by internee Ryozo Kado in 1942.

On February 19, 1942, just two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, effectively setting up military camps and allowing for the forcible removal of more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans from their homes. Truth is, the government had been preparing a tent city for potential prisoners at Manzanar, calling it Camp Owens, as early as June 1941, half a year prior to the Japanese attack. Also, a list of United States Nisei (second-generation Japanese-Americans) was delivered to President Roosevelt, per his request, about a week before 12/7/1941. Clearly, the mass internment was not just a reaction to the Pearl Harbor bombing.

Above: the middle shot is the location of the camp's baseball fields, the lowest are ruins of the John Shepherd Ranch. Shephered had his orchards here from 1864 - 1905.

The man who oversaw the relocation was the Army’s West Coast Commander, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, a poster child for the abuse of civil liberties if there ever was one.

About two-thirds of all those eventually incarcerated at Manzanar were American citizens by birth. Many of them received as little as four days notice to get rid of what they owned and be prepared to be relocated either initially to temporary assembly centers, like the one at the Santa Anita racetrack, or, later, directly to Manzanar.

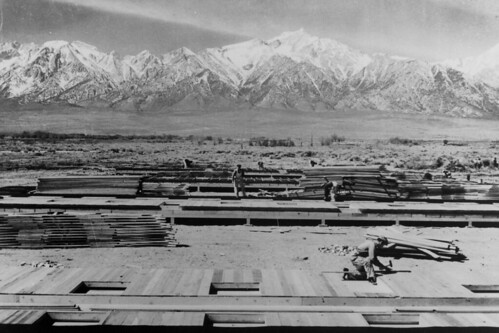

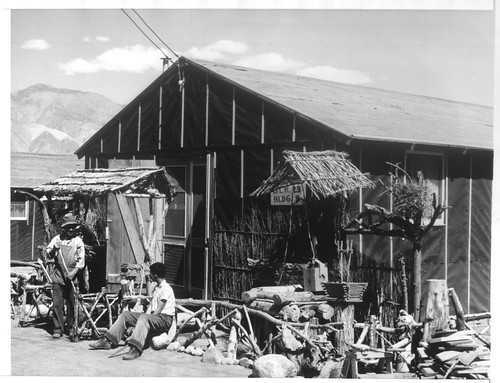

From top to bottom: the camp under construction, photo by Clem Albers, 4/2/42; some of the remaining fruit trees planted by the Owens Valley Improvement Company around 1910; Block 34's mess hall garden.

By the time the U.S. Army leased 6,000 acres for the relocation center, the agricultural town of Manzanar (Spanish for apple orchard) had been deserted for about seven years, since a few years before that, in 1929, the city of Los Angeles wrapped up acquiring the town’s land and water rights. (What L.A. did to the Owens Valley, of course, is almost as hilarious as the story of the war camp itself. And, unless I’m wrong, the city profited from the feds leasing the land during WWII, too. Right?)

From top to bottom: that's the camp's morgue over to the left; the site of the laundry room; and Children's Village. Sisters Mary Suzanne and Mary Bernadette ran Children’s Village, taking care of the center's fifty or so orphans. The two had previously run a Los Angeles orphanage for children of Japanese ancestry.

New camp residents were met with barbed wire fences and eight guard towers manned by military police with submachine guns and searchlights. Armor and Wright, in their book, Manzanar, describe the housing conditions:

“The main camp at Manzanar consisted of 560 acres, on which were constructed nine wards of four blocks each. Each block contained sixteen barracks, or one-story buildings, twenty by one hundred feet. Of the sixteen buildings, fourteen were residential, one of double size was the mess hall, and the last was a meeting/recreation hall.”While the spaces of twenty by twenty-five feet were designed for families of four, the average held eight people, sometimes reaching eleven.

The remaining 5,500 acres held military police housing, a reservoir, a sewage treatment plant, and agricultural fields.

From top to bottom: Block 23, Building 29; site of Block 3, home to 227 Japanese-Americans from Bainbridge Island, near Seattle; the Kendo Dojo.

The War Relocation Authority took over operation of Manzanar from the U.S. Army on June 1, 1942. Later that year, in December, military police shot to death two detainees and wounded ten others during a protest.

From top to bottom: the pet cemetery; the cemetery monument; remaining graves. About 150 Japanese-Americans died at Manzanar. Only fifteen were buried here; most of the others were cremated. Today, only half a dozen are still buried in the cemetery. Because individual gravestones were not affordable, the Manzanar Cemetery Monument was dedicated in August 1943. Its inscription reads, “Memorial to the Dead.”

The camp’s population began to decrease as prisoners received work passes and young men volunteered for service in the armed forces (go figure). Also, in December 1944, the Supreme Court ruled loyal citizens could not be detained in detention centers against their will. The Manzanar War Relocation Center finally closed on November 21, 1945. Freed prisoners were given train fare and $25. Following the war, nearly all of the camp’s 800 buildings were dismantled or relocated.

Top to bottom: warehouse area; Dorothea Lange photo, 6/9/42; the net factory, where internees made camouflage netting for the U.S. military.

Geographically, Manzanar is located in the Owens Valley between the Sierra Nevadas on the west and the Inyo Mountains on the east. The big mountain you see in these shots is not Mt Whitney. Whitney’s nearby, but this peak is Mt Williamson, just more than 100 feet shorter than Whitney.

Top to bottom: Mt Williamson; site of the Manzanar Free Press; the location of Manzanar High School; and Blocks 9 and 10. The Manzanar Free Press was launched on April 11, 1942, edited by Roy Takeno, and ran until New Year’s Day, 1944. Manzanar High opened in October 1942 and graduated classes the following three years. Some of the camp's first prisoners, from Terminal Island near San Pedro, were housed in Blocks 9 and 10.

In addition to its Los Angeles HCM status (one of only two outside the city), Manzanar today is recognized as a California Historical Landmark, a National Historic Landmark, and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In 1997, the National Park Service bought more than 814 acres of Manzanar land from Los Angeles.

Today, the Manzanar Interpretive Center (above) is in the camp’s old high school auditorium-gymnasium. Built by detainees in 1944, it later served as a V.F.W. social hall and then a garage and shop for the Inyo County Road Department. It opened as the current wonderful and moving museum in April 2004. The museum, the military police sentry post, the internal police post, and the cemetery memorial are the only remaining structures of the Manzanar camp. (An old mess hall was moved to the site in late 2002 and is not original to the camp.)

You owe it to yourself to explore the Park Service’s official Manzanar site. Or, better still, visit Manzanar in person. You might want to choose a better time of year than summer. I spent around three hours walking the site on that brutally hot Saturday back in June, and I’m still drinking fluids like hotcakes.

Sources:

Houston, Jeanne Watkatsuki and James D. Houston Farewell to Manzanar Laurel-Leaf 1973 New York

Armor, John and Peter Wright Manzanar Times Books 1988 New York

Up next: Wolfer Printing Company

13 comments:

I recall many years back reading an article that spoke of broken crockery from the mess hall found abandoned. I wonder if some of that crockery is on display at the museum?

Your photos are beautiful and convince me that I should stop and visit on my next trip up 395.

I've seen signs for this place for years but never stopped by. I had no idea how fascinating it is. I'm definitely putting it on the to-do list. Oh, your shots of the Sierras are truly beautiful.

Thanks, P.A. and G.C. I arrived late at night, stayed at a motel, and walked out the next morning slammed up against the Sierras. Really beautiful. There's also a fun museum in Lone Pine which chronicles the area's history with Hollywood, everything from the silents to Gunga Din to Iron Man.

You've added quite a bit of new area to the Google Map. Thanks for keeping on this and sharing the journey with all of us...

Hey, Renegade. This will probably throw your map way off, no? In any event, you're the one to be thanked for keeping up the map project. So, thanks.

Another connection to the silent film era is the Rossi family. They own Rossi's Steak and Spaghetti House in Big Pine (rated the 17th best steak in California!). Italian immigrants whose background was in stonemasonry. On one of the local trails is a stone cabin now in the hands of the forest service. I believe it was built for silent film star Tom Mix by one of the the Rossi's way back when. Beautiful work. Also worth noting is a Nuetra house in Lone Pine.

Had I know about the Neutra house, I would've tracked it down. Same with the steak house. Now, a Neutra house that serves steak would be too overwhelming.

I just passed by Manzanar 2 weekends in a row. It boggles the mind on how the relocation could have happened and driving by the site is always a good reminder to keep vigil. Last year, we The museum in Independence has an excellent display of life & art by the Japanese in the camp.

No kidding about the vigil part, Tash. I've talked to no one about Manzanar without someone saying how it could happen again. The camp being located so close to Independence, CA, is one of the state's history's great contradictions.

Hello Floyd -- A personal note about Manzanar. My mother was about 18 years old in 1942. There were many Japanese Americans living in San Pedro, CA that year. One of my mother’s best friends was one such individual, a Japanese American girl also about 18 years old. I wish I remembered her name, and my mother passed away 2 years ago or I’d ask her. My mother remembers the day her friend was removed and taken to Manzanar. She lost track of her during the war years, and after the war, none of those relocated to the camp ever returned to San Pedro. After all, all their property had been confiscated. Although a sad footnote of our history, the reason given by FDR, was not only for fear of espionage and sabotage, but also for their protection. After all, the hatred thru propaganda was so strong in the mainstream population, that the Japanese American families could have been at risk of retaliation and bodily harm. Nevertheless, I have seen documentaries about Manzanar, and the inexcusable part is that the camp was not very accommodating. They did not take into account the Japanese American diet, and served food that they could not or would not eat. They also did not account for the internees sense of modesty and built communal bathrooms. The toilets were aligned in a row without dividing partitions. One internee recounted their solution to this problem. Everyone entered the bathroom with a paper shopping bag and put it over their heads for privacy while doing their business. And of course we know how the Japanese American young men enlisted in the Army and were sent to Italy to fight in that campaign. Yet, what might be an interesting side note, the Japanese in Hawaii were not interned. I have a friend whose father, a Japanese American from Hawaii, enlisted in the Army and was sent to the Pacific as a translator. He was at Okinawa encouraging the civilians and military to surrender, that they would not be harmed. It was there that the military were committing Hari Kari and the civilians were jumping off the cliffs. My friends mother, an Okinawan, hid in a cave during the occupation, and later met and married, my friends father, the Army interpreter. Question for you Floyd, what is the inscription on the monument at Manzanar? Thanks -- Robert Reed

Thanks for the comment, Robert. The inscription reads "Memorial to the Dead".

Very interesting. My mother's father was the son of German immigrants, and they lived in a German area in Orange County. My mothers says that when the Japanese were rounded up, the Germans were terrified that they would be next.

Thanks, Rosemary. My family was in the same boat as yours, but since they didn't look different like the Japanese, I'm not sure they had as much to fear.

Post a Comment