Saturday, February 28, 2009

Heritage Square Turns 40

On Saturday, March 7, help Heritage Square Museum celebrate its 40th anniversary.

It was on March 6, 1969, Monuments Nos 5 and 27 – the Salt Box and the Castle – were moved from on Bunker Hill to the Square (of course, they weren’t there long). The anniversary event begins at 2:00 p.m., costs ten bucks, and will feature talks by freshly re-elected City Councilman Ed Reyes and Dr Robert Winter, a long-time member of the Cultural Heritage Commission, a Heritage Square co-founder, and Los Angeles’s premiere architectural historian. Plus, I’m looking forward to the unveiling of the rebuilt veranda on HCM No. 413, the Longfellow-Hastings Octagon House, pictured above between the Ford House and the Palms-Southern Pacific Railroad Depot, both city landmarks. The original veranda was removed more than ninety years ago. You can find more information at the Heritage Square blog.

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

9:47 PM

2

comments

![]()

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

No. 217 - Wicks Residence

Wicks Residence

c. 1895

1101 Douglas Street – map

Declared: 6/6/79

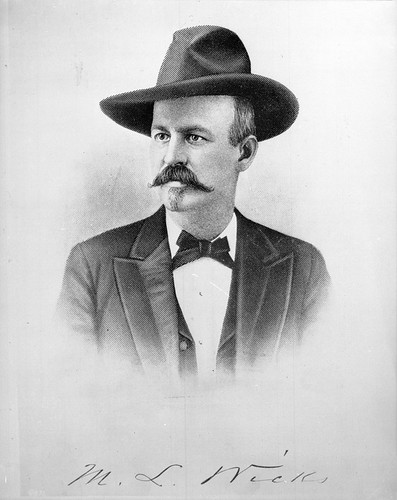

Here’s an Angelino Heights house built around 1895 for “smooth speaking” “gentleman of vision” M.L. Wicks. Regarding Wicks and Los Angeles, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in his History of California (1884-90), wrote there were “few prominent enterprises in this portion of the state in which he has not been one of the leading promoters.”

Moses Langley Wicks was born in Aberdeen, Mississippi, in 1852. He moved with his family to Memphis, graduated from college as an accountant, and got a law degree from the University of Virginia. In 1875, Wicks married Elizabeth Littlejohn. The couple followed his father to L.A., then moved down to Anaheim where Wicks set up law practice. Elizabeth died shortly after giving birth to Moses, Jr., but Wicks remarried in 1881 and had another son, Percy Langley. M.L. returned to Los Angeles in 1877, residing at 121 South Fort Street (now Broadway). (His investment in Fort property paid off in 1886 when, along with L.H. Titus and Howard W. Mills, Wicks sold to the city for $34,000 the land for a new City Hall (1889) between 2nd and 3rd.)

M.L. Wicks, from USC Libraries Digital Archive

By the mid-1880s, after helping to found the Los Angeles Bar Association, M.L. Wicks had fairly well left lawyering to live in the world of real state and transportation. (Don’t confuse Moses with his brother, Moye, an L.A. attorney in the firm of Wicks, Lucas, and Bentley. And now for something completely different: Moye and his pistol once took a couple of shots at J.H. Levering in the County Clerk’s office, but was soon exonerated; turns out he didn’t mean to hurt the guy. Moye eventually moved to Washington state.)

From L.A.’s Department of City Planning

Wicks played various parts in the development of Glendale, San Dimas, Garvanza, Highland Park, Edendale, sections of downtown L.A., and San Bernardino. His primary platting: Eagle Rock and Linda Vista as part of Benajmin Dreyfus’s old Rancho San Rafael; the Dalton portion of the San Jose Rancho which he’d bought from Jonathan S. Slauson et al for $255,000; Pomona; and the Playa del Rey section of Rancho La Ballona. In 1884, Wicks bought land from the Southern Pacific for $2.50 an acre (cheap!) and laid out the town of Lancaster. Four years later, Wicks sold just about the whole town to James P. Ward for $46,620, or about $20 per acre.

Wicks became affiliated with the Temecula Land and Water Company, and, according to author Glenn S. Dumke, he was “interested in the Savings Fund and Building Association of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles and Santa Monica Railroad, the Abstract and Title Insurance Company, and the California Bank.” Wicks put the first $50,00 into the Los Angeles County Railroad Company (of which he was first president), and sunk another $120,000 in to Ballona Harbor which he saw as a shipping point to compete with the Southern Pacific’s Santa Monica wharf. Wicks served as President of both the Citizens’ Water Company and the Sunset Boulevard Improvement Association. He was the “principal promoter of the Red Car Line” and tried several times to connect downtown L.A. to the coast by rail.

It wasn’t all a bed of roses for Wicks. His 1887 subdivision of Hyde Park – a “midway town between the city and the harbor” – failed. A dozen years later he filed for bankruptcy (an L.A. Times article reported “Wicks was insolvent and heavily involved in debt as afar back as December 25, 1887, when his liabilities aggregated $200,000.”)

Historic-Cultural Monument No. 217, this 1895 house is primarily Queen Anne in design with a few hints of the Colonial Revival. Wicks lived here until about 1915.

Moses Langley Wicks died in late 1919 as a result of injuries suffered after being struck by a car at Hollywood and Vine (construction engineer Louis C. Hill of 2144 Canyon Drive was behind the wheel). Poor M.L. then fell and konked his head on a steel streetcar rail, cracking his skull. At the time, Wicks had been living at 1918 Miramar Avenue.

Sources:

Bancroft, Hubert Howe History of California The History Company 1894-90 San Francisco, CA

“The Shooting.” The Los Angeles Times; May 22, 1886, p. O_2

“The City Hall.” The Los Angeles Times; Sep 18, 1886, p. O_4

“Council.” The Los Angeles Times; Oct. 1, 1886, p. O_4

An Illustrated History of Los Angeles, California Lewis Publishing Co. 1889 Chicago, IL

“Decided to Annex.” The Los Angeles Times; Jun 30, 1895, p. 22

“Pursuit of Property.” The Los Angeles Times; Apr 7, 1900, p. I10

“Second Ward Federation.” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 21, 1908, p. II6

“Explains Politics of the Henderson Appointment” The Los Angeles Times; Jul 28, 1912, p. II1

Newmark, Harris Sixty Years in Southern California 1853-1913; The Knickerbocker Press 1916 New York, NY

“Aged Realty Dealer Hurt by Automobile.” The Los Angeles Times; Dec 4, 1919, p. I8

Dumke, Glenn S. The Boom of the Eighties in Southern California Huntington Library 1944 San Marino, CA

“City Hall Site Purchased in Early Days for Trifle” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 17, 1929, p. E1

Robinson, W.W. Lawyers of Los Angeles; a history of the Los Angeles Bar Association and of the Bar of Los Angeles County Los Angeles Bar Association 1959 Los Angeles, CA

Lombard, Sarah R. Rancho Tujunga: a History of Sunland-Tujunga, California Sunland Woman's Club c. 1990 Sunland, CA

Wayte, Beverly At the Arroyo’s Edge: a History of Linda Vista Historical Society of Southern California and Linda Vista/Annandale Association 1993, Los Angeles, CA

Up next: Politi Residence

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

9:37 PM

0

comments

![]()

Saturday, February 21, 2009

No. 216 - Hall Residence

Hall Residence

1887

917 Douglas Street – map

Declared: 6/6/79

Angelino Heights – originally spelled Angeleno Heights, with an ‘e’ – was first developed by two men: William W. Stilson and Everett E. Hall. Having bought the land from Victor Beaudry and his partners (Victor Heights was right next door), the duo filed for subdivision on March 19, 1886. Stilson would be the money man while promotion would be Hall’s territory. Stilson built his thirty-room mansion on the northwest corner of East Edgeware Road and Carroll Avenue. It’s still there, too, but a modernization from half a century ago has rendered the home unrecognizable. Hall and his wife, Nellie, initially moved into a place close by on Edgeware, but very soon after settled into this house on Douglas Street (then called Waters Street). Unlike the Stilson mansion, it remains much more authentic (if in need of a paint job) and is Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument No. 216.

Hall, from Ionia, Michigan, was an attorney and president of the Los Angeles and Pacific Railway Company. When he moved to this future landmark his estate stretched from Kellam to Edgeware. Included on the property was Hall’s carriage house. Though still in the same spot, the carriage house now belongs to 1417 Kellam Avenue around the corner. It’s HCM No. 166.

From L.A.’s Department of City Planning website.

The two-story house is Eastlake in design and features an Oriental fret pattern along with its L-shaped porch. And if posting the year of construction on the side of your home were a law in L.A., it’d make things a whole lot easier for bloggers who list the year of construction on the line after the address.

Hall fell on hard times shortly after moving into the house. He began selling off chunks of his property, then the home itself. Subsequent residents of 917 Douglas included members of the Heim Brewing Company’s Heim family (another Heim, Ferdinand, owned HCM No. 77 nearby on Carroll Avenue), future Glendale bigshots Leslie C. Brand and Daniel Campbell, and Ida Millard, sister of Everett Hall and widow of Spencer Millard, Lt Governor of California (also from Ionia, Michigan). And a contemporary city directory tells us widows Amelia M. Knox and Helen Marmion were living there in 1915.

Some more information with which to stymie your enemies: besides through the city landmark, Everett Hall and his family live on through a few street names in and around Angelino Heights. Allison Avenue is named for Hall’s younger brother, and Marion Avenue for a daughter who died in infancy. And there’s nearby Everett Place, Everett Street, and Everett Park. (Wallace and Carroll took the names of Stilson sons.)

Sources:

“Spencer C. Millard Dead: A Farmer’s Son Who Became California’s Lieutenant Governor.” The New York Times; Oct. 26, 1895, p. 9

Los Angeles City Directory 1915 Los Angeles Directory Company, Los Angeles, CA

Morales, T.M. “Neighborhood ‘Dandy’ now Disguised ‘Victorian’” Parkside Journal Oct 3, 1979, p. 1

An Album of Significant Homes in Century-Old Angelino Heights 1987 The Carroll Avenue Restoration Foundation

Morales, Tom Angelino Heights Preservation Plan – Section 4.1 History of Angelino Heights; June 10, 2004 p .9

Up next: Wicks Residence

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

9:07 PM

9

comments

![]()

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

City of the Seekers: L.A.'s Unique Spiritual Legacy

L.A. Historic-Cultural Monument No. 845, Mount Washington Hotel/Self-Realization Fellowship International Headquarters

Your reading this post makes me think you already know the Los Angeles Conservancy is sponsoring a self-driving tour of “five historic sites related to spiritual organizations that took root in Los Angeles in the early part of the twentieth century.” The sites are: Angelus Temple; the Self-Realization Fellowship Mother Center; Chapel of the Jesus Ethic; the Philosophical Research Society; and the Bonnie Brae House, home of the Pentecostal movement.

Two of the stops – the Philosophical Research Society and the Self-Realization Fellowship Mother Center (the former Mount Washington Hotel, pictured above) – are Historic-Cultural Monuments, and I’m going to take full advantage of the Conservancy tour to visit them (even though I won’t be blogging about them until, like, 2012 and 2015). I’m also planning on getting the answer to why Aimee Semple McPherson’s Angelus Temple is not a city landmark, despite being both listed on the National Register of Historic Places and one of just seven National Historic Landmarks located in L.A.

The tour is March 14, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Go here for more information and tickets, please.

The shot of the Mount Washington Hotel is from the Los Angeles Public Library online photo archive.

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

11:05 PM

2

comments

![]()

Friday, February 13, 2009

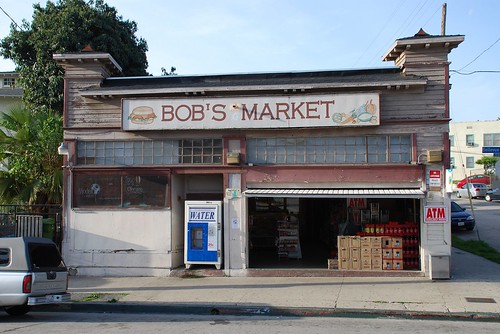

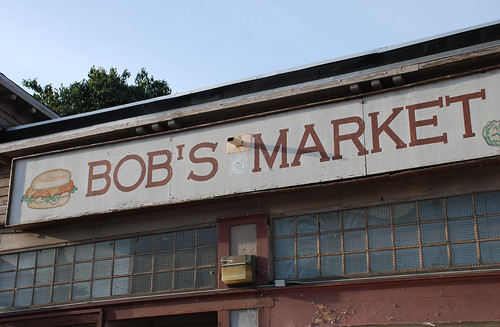

No. 215 - Bob's Market

Bob’s Market

1913 – George F. Colterison

1230 Bellevue Avenue – map

Declared: 6/6/79

Okay. Add the proprietors of Bob’s Market to the list of those who do not appreciate my taking photos of their establishment, in this case a city landmark for nearly thirty years now.

In 1913 Ella J. McMillen hired architect George F. Colterison to design for her what would be this one-story, false front, frame structure with slight Mission Revival and Oriental elements. Peter A. Holmberg’s construction costs ran the Widow McMillen $3,500.

The sight was absolutely perfect for a grocery store, located at a six-point intersection in the paths of trolleys, carriages, and pedestrians. Now, at first, the building housed two businesses (and two families). One of the first tenants/shop-owners was Levon Melkonian. He fled the Turks and the Armenian Genocide in 1914, setting up a tailor shop in the 1253 Bellevue half (his wife, Azniv M., joined him five years afterwards). Levon was on the other side of grocer Frank E. Sandberg. Abram and Miriam Kooper bought the grocery half in 1926, establishing a home there the following year. In 1934 the Koopers acquired the dry cleaning business next door from Fred and Nelly Baalberger. Since then, the building’s held a single business.

Kensington Properties bought the landmark on January 11, 1963. Two years later, Bob and Keiko Nimura bought it from Ben Nakone.

Bob’s Market narrowly escaped a devastating six-house fire on the block in August 2003. The blaze left nearly thirty residents homeless.

McGrew and Julian, in their Landmarks of Los Angeles, say Bob’s Market is “unique primarily because it has survived”, but what they don’t say is that Angelino Heights at one time had four local grocery stores, one of which was around till not that long ago.

Even those of us with only a passing knowledge of Angelino Heights remember the B & K Market at the northwest corner of Bellevue and West Edgeware. You can still see the shop’s sign telling us Knudsen is The Very Best (and you can make out the B & K on the sign if you get up really close). Ninety-plus years ago, this grocery was run by a man named Henry M. Reuter. He lived right behind his shop at 1166 West Edgeware.

Henry Reuter’s grocery store / B & K Market

For those of you who can remember back twenty-five years, you might recall the shop at 826 East Edgeware, between Carroll and Kellam. A plaque on the building’s side tells us it was a community store from 1911 to 1984. In 1915, this was the Driggs Bros market. That year, brothers B. Ruggles and John W. were living at nearby 816b East Kensington and 1100 West Kensington, respectively. Here’s the Driggs Bros store today:

The Driggs Bros market

Thirdly – and most obscurely – there was Harry Smookler’s grocery at 954 East Edgeware. Harry bought the land – lot 5, block 11 – from Charlie Stimson in 1906. Smookler also lived here with his family.

Former Harry Smookler store/residence

Poor Harry. Just a few days before Christmas 1912, the neighborhood grocer gave his son, Willie, what the Los Angeles Times called a “slight chastisement”. A sensitive lad, distraught fifteen-year-old Willie subsequently borrowed a pistol from his pal, Waldo Hardeson, who then accompanied his buddy to buy cartridges. The teenage Smookler walked to a nearby vacant lot, stuck the gun in his mouth, and committed suicide. Harry the grocer found the body.

Sources:

“Houses, Lots and Lands – Review of Building and Development” The Los Angeles Times; Jun 10, 1906, p. V24

“Youthful Pride Causes Tragedy.” The Los Angeles Times; Dec 20, 1912, p. II5

Morales, T.M. “Family Operated Stores Still Stand” Parkside Journal; Jul 25, 1979, p. 1

McGrew, Patrick and Robert Julian Landmarks of Los Angeles Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1994 New York, NY

Rubin, Joel and Monte Morin “Fire Chars Angelino Heights Homes” The Los Angeles Times; Aug 15, 2003

Up next: Hall Residence

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

11:37 PM

7

comments

![]()

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

No. 214 - (Site of) Mt Carmel High School Building

(Site of) Mt Carmel High School Building

1934 – Barker & Ott

7011 South Hoover Street – map

Declared: 6/6/79

Construction began in the late spring of 1934 on this two-story, late Spanish Colonial Revival school building, designed by Merl Lee Barker and G. Lawrence Ott for the Missionary Society of Our Lady of Mount Carmel of the Carmelite Order of New York. It’s been gone going on nearly thirty years now, so if there are any Mt Carmel graduates out there, it’d be great to hear from you.

The thirty-four room structure, constructed of reinforced concrete, was the first school in Los Angeles built to new seismic standards following the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. Laurence J. Waller was the structural engineer, W.W. Petley got the general contracting gig, and the F.D. Reed Company handled the plumbing. The school’s size was 13,920 square feet, and it sported a stucco exterior.

The $85,000 to $100,000 building was dedicated on January 6, 1935. Rt Rev. John J. Cantwell, bishop of the Diocese of Los Angeles and San Diego, laid the cornerstone and gave the dedicatory address. Father Flannagan gets credited with the school’s founding.

The Reverend Niles J. Gillen announced in April 1976 the all-boys school, operated by the Catholic Fathers of the Order of Mt Carmel, would close due to decreasing enrollment, down to 276 from more than 600 in the early 1960s. A group of parents organized a petition drive to convince the Chicago-based Carmelites to change their minds but to no avail. Plans even called for asking Pope Paul VI to intervene. And hopes the L.A. Archdiocese would take over the school never panned out. Mt Carmel shut down with the end of the school year on May 26.

As part of its Historic-Cultural landmarking, South Central’s Mt Carmel High School was called by the city, “an excellent example of Mission architecture housing a school which has made a significant contribution to the community.” It looks like the 1979 monumental status was conferred primarily to ward off the school’s destruction by the Parks and Recreation Department which had owned the building by that time.

I’ll admit I’m more than a bit sketchy about how the landmark eventually met its demise. The gym remained until a fire brought it down in 1983. By this time, though, the school building had already been demolished, maybe the previous year? Perhaps it had served as a senior center in its post-school years? In any event, the city’s Office of Historic Resources has no record of any demolition permit being issued. If you know anything, fill us in, please.

The sole picture is from the L.A. Department of City Panning’s website.

Sources:

“School Constructions Ready To Be Launched” The Los Angeles Times; May 20, 1934, p. 21

“Catholics Today Will Dedicate New High School” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 6, 1935, p. 15

“Mt. Carmel High School to Close Doors in June” The Los Angeles Times; Apr 3, 1976, p. A27

Fanucchi, Kenneth “’It’s Too Late’ To Save School” The Los Angeles Times; Apr 18, 1976, p. CS1

Fanucchi, Kenneth “Parents Fight Mt. Carmel Closing” The Los Angeles Times; Apr 22, 1976, p. CS1

Up next: Bob’s Market

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

11:08 PM

8

comments

![]()

Labels: South Los Angeles

Saturday, February 7, 2009

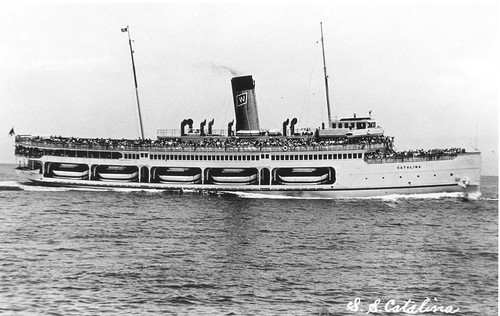

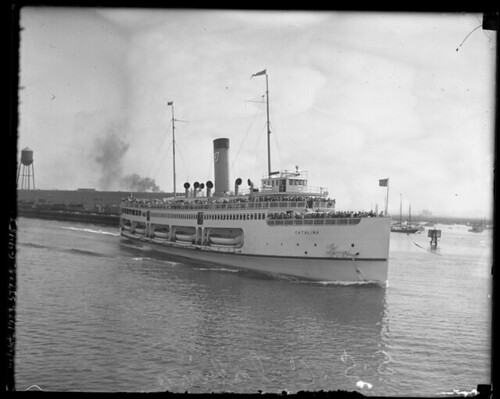

No. 213 - S.S. Catalina

S.S. Catalina

1924, cut for scrap in 2009

Declared: 5/16/79

Talk about great timing. I missed visiting Monument No. 213, the S.S. Catalina, by this much. The bags were packed, the tank was full, the passport – eh, let’s face it. There’s not a chance in hell I would’ve made the 180-mile trip down to Ensenada to see and be saddened over what was left of the eighty-five-year-old “Great White Steamship”. Unfortunately, I (and you) will never get the chance now.

In 1919, five years after Doublemint’s debut, Cub-and-gum man William Wrigley Jr purchased Santa Catalina Island and the Wilmington Transportation Company from William, J.B., and Hancock Banning, sons of Phineas. To turn Catalina into the resort he envisioned, Wrigley needed a bunch of boats to ferry passengers between the mainland and the island’s city of Avalon. He had already gotten a pair of ships as part of the Wilmington Transportation Company – the Hermosa (1902) and the Cabrillo (1904). And, after World War I, Wrigley purchased from the U.S. Navy the U.S.S. Blueridge, built by the Globe Ironworks of Cleveland in 1891 and originally christened the Virginia. After a major refurbishment, this last ship was renamed the S.S. Avalon in 1920. But Wrigley wanted a fourth.

Here are pictures of the Cabrillo (courtesy of USC’s Digital Archive) and the Avalon (from the L.A. Public Library). Like the Catalina, both ships served in World War II, the Avalon staying in SoCal, the Cabrillo eventually making its way to Sacramento. The latter was left to rot and be cut for scrap near Napa. The Avalon was retired in February 1951. Nine years later, this ship, too, was cut for scrap, then suffered a fire, ultimately sinking off Palos Verdes in 1964.

William Wrigley Jr laid the keel of the million dollar S.S. Catalina at the L.A. Shipbuilding and Drydock Harbor on the day after Christmas, 1923. Just four and a half months later, on May 3, 1924, Mayor Cryer and 3,000 onlookers watched Miss Marcia Patrick, the sister of the Wilmington Steamship Company’s president, christen the ship. With A.A. Morris its captain, the Catalina left her Berth 185 homeport in Wilmington on June 30.

The S.S. Catalina stretched 301 feet long and fifty-two-feet wide. It weighed 1,766 tons. There were five decks, three of which were for passengers: the Promenade; the Saloon; and the Main. The top deck held the bridge with the pilot house and captain’s cabin.

During the Catalina’s two-hour trip to Avalon’s Steamer pier, its passengers (the ship had a capacity of 2,200) could dance to a big-band orchestra while clowns and magicians would entertain their kids. In 1929, the Cabrillo, Avalon, and Catalina, making a total of ten daily roundtrips, carried a combined half a million passengers between L.A. Harbor and Santa Catalina Island. (Wrigley sold the Hermosa in 1928.)

William Wrigley, Jr, died in 1932 and his son, Philip, inherited the company.

During World War II, the government drafted the S.S. Catalina into service, designating the ship as FS-99 for use as an Army Troop Transport. Employed in San Francisco Bay, the steamship wound up ferrying soldiers to larger warships. In her forty-four months of military service, the Catalina transported some 820,000 men, more than any other U.S. Army Transport. The ship was back to its old L.A. to Santa Catalina run on July 3, 1946.

S.S. Catalina, troops (L.A. Public Library)

At the beginning of 1948, the Wilmington Transportation Company changed its name to the Catalina Island Steamship Line. During the 1950s, there were now just single daily roundtrips made from Wilmington to Santa Catalina. In 1956 it would cost you around $6.00 for a roundtrip ticket. The Wrigleys sold the steamship line to Charles Stillwell and his M.G.R.S. Company, Inc., in 1960. Stillwell sold the Catalina – now with its terminal under the Vincent Thomas Bridge – in 1970 to Carolyn Stanalan and her family.

The S.S. Catalina completed her 9,807th and final crossing on September 14, 1975. Real estate developer Hymie Singer bought the ship for $70,000 at auction on February 16, 1977, as a belated Valentine’s Day gift for his wife, Ruth. The new owners struggled with docking fees, mooring the former ferry in San Pedro, Newport Beach, San Diego, and Santa Monica Bay, then settling the vessel off Long Beach for five years. An attempt at rehabilitation failed in 1983. Two years later, after the ship broke free of its moorings in a second instance – this time nearly causing a major accident, the Coast Guard had had enough and announced it was going to seize the Catalina. The owners opted to remove the ship from U.S. waters, and by the spring of 1985, the boat was three miles off the coast of Ensenada, Mexico. The Catalina Bar and Grill Restaurant opened on board the L.A. landmark in the summer of 1988, but didn’t stay in business long.

Over the next two decades, the S.S. Catalina, “the Great White Steamship”, slowly deteriorated, rotting, sinking, and listing, thanks to looters and thieves, the Mexican government (which had ordered the boat’s solid bronze propellers removed, allowing seawater to seep into the ship), neglect, and plain old ravages of time. Spare half a minute and watch this video of the Catalina in Ensenada, by this time a home for sea lions.

The Singers gave up ownership of the Catalina and, in 2000, the Mexican government donated the boat to the S.S. Catalina Preservation Association for non-commercial preservation purposes. Despite salvation efforts from a variety of concerned groups including the Raising the Catalina Association and the S.S. Catalina Steamship Fund, the Mexican government began cutting apart the ship for scrap just a few weeks ago.

It’s figured the S.S. Catalina alone carried 25 million people in its service of fifty-one years, maybe more than any other ocean-going ship in history. Besides being designated a city landmark in 1979, the ship was also listed on the National Register of Historic Places and declared a California State Landmark.

A very big thanks to Shawn J. Drake for his online essay, “The S.S. Catalina: the First 75 Years of a “Great White Steamer””. The shot at the top of the post is from the L.A. Department of City Planning, while the one below is from UCLA Library’s Digital Collection.

Sources:

Pool, Bob “SS Catalina is Seaworthy No More” The Los Angeles Times, Jan 6, 2009

Up next: (Site of) Mt Carmel High School Building

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

9:56 PM

8

comments

![]()

Labels: Outside City of Los Angeles

Wednesday, February 4, 2009

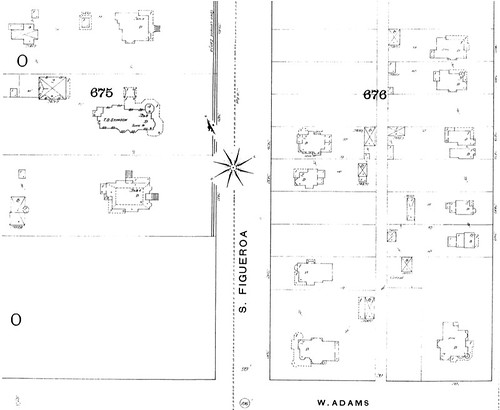

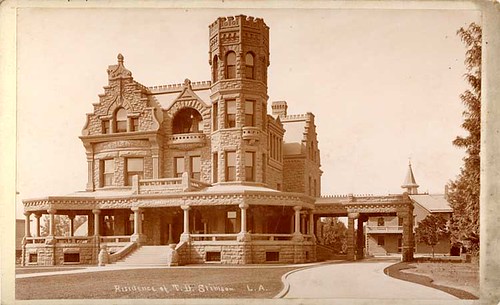

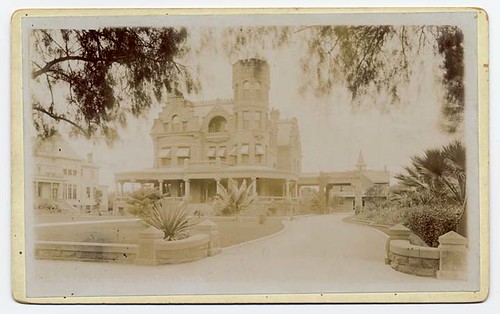

No. 212 - Stimson Residence

Stimson Residence

1891 – Carroll H. Brown

2421 South Figueroa Street – map

Declared: 5/16/79

Historic-Cultural Monument No. 212 is the sole remaining mansion on what was, a hundred years ago, a long stretch of stately homes known as “Millionaire Row” on South Figueroa Street. If there could be only one left standing, though, I reckon it should be this one, a home the Los Angeles Times once called “the costliest and most beautiful private residence in Los Angeles.” The city says it’s the only example of Richardsonian Romanesque architecture remaining in Los Angeles.

Thomas Douglas Stimson was born in French Mills, Canada. He left his childhood home in New York at the age of fourteen, later working as a trader in a Muskegon, Michigan, lumber camp. He went on to further his fortune in Chicago before retiring to Our Fair City in 1890. Here he quickly set to hiring to design this three-and-a-half-story, thirty-room mansion on the eastern edge of West Adams a young architect by the name of Carroll H. Brown.

Brown was born in Illinois in 1863. By the time he worked on the Stimson Residence, although he was only twenty-seven-years-old, he was already a prominent SoCal architect, having designed downtown mansions for Louis Shiveley, H.L. MacNeil, and W.A. Clark. He also created a $7,000 monument in Wilmington for Gen. Phineas Banning. Within the next few years, the architect would go on to build the first home for the California Club, Santa Monica’s Keller Block building on Broadway, and T.D.’s six-story Stimson Block at 3rd and Spring, the largest office building in L.A. at the time (demolished in 1963). He was a charter member of the Architectural Association of Southern California, formed in 1892 and which became the Southern California Chapter of the AIA two years later. Brown became its president in 1907. He died in L.A. in 1920.

Brown’s Stimson Block

I know I’ve been including lots of Sanborn fire insurance maps lately, but here’s one more from 1894. Check out the “open cement zanja” running through Stimson’s front yard. And I don’t know when the city removed that big star lying in the middle of the street, but I’m glad they did.

Stimson’s new 12,800 square-foot home (the square footage not including the crenellated tower) covered in red Arizona sandstone cost him anywhere from $130,000 to $200,000, as I’ve seen it pegged at a few different prices (I’d think it were more toward 130 g’s; while that was still a lot of money in those days, 200 grand was a lot of lot of money). This new home of the former lumberman consisted of room after room paneled in an incredible variety of woods, including ash, walnut, sycamore, birch, gumwood, mahogany, oak, and something called monkeypod.

I’m including the following three vintage shots, each for a different reason. The top photo, from the CA State Library, is the earliest of the landmark I could find. It shows the northern side of the building, a view obscured today. The next, from the same source, is from around 1895. What’s extra cool about this one is it shows a glimpse of L.A. City Councilmember Frank Sabichi’s home next door. Frank’s house, like the rest of the mansions along South Fig, is long gone, today the parking lot for St Vincent de Paul’s. Finally, there’s a later picture of the Stimson Residence. This one, from the L.A. Public Library, shows off that zanja running along the front of the property.

The biggest event in the landmark’s 128-year history occurred just about this time of year in 1896 when, at 10:30 p.m. on February 6, someone placed “a stick of giant powder… against the foundation of the building on the south side, just in rear of the front veranda” causing a huge explosion “heard for miles around.” There were no injuries sustained in the dynamiting, and “the stately architectural pile was scarcely even shaken.” It was also reported T.D. came “out of the house… viewed the hole torn in the ground at the side of the house… laughed softly and retired to his castle.”

A month later, private detective Harry L. Coyne was arrested for the crime. The reasoning behind the deed seems the stuff of the better Columbo episodes. Coyne, having escorted Stimson’s son to Mexico City, told T.D he had uncovered a plot against the retired lumberman/financier. Following the dynamiting, Coyne offered to give information regarding the crime to Stimson, but for a price. After offering to police to implicate three men in the crime for sixty dollars, Coyne went back to Stimson and demanded $250. Ultimately, though, Coyne’s knowledge of the crime’s details did him in. He was sentenced to five years in Folsom.

T.D. Stimson died in the house on January 31, 1898, at the age of seventy (“the smoothest pickpocket in the city”, “Mother” McGarey, attended the funeral to practice her vocation, but was thwarted by mourner Police Chief Glass). Stimson’s family remained in the house until 1907 (or maybe 1904) when they sold it to civil engineer Albert Solano. Edward Maier, the owner of both the Maier Brewing Company and Hap Hogan’s Vernon/Venice Tigers of the Pacific Coast League, bought the home in 1918, hosting parties with guests including the likes of Jack Dempsey, Barney Oldfield, and Burbank’s Boilermaker, Jim Jeffries.

The Carriage House

In 1940, USC’s Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity bought the former Stimson estate for a cool $20,000, mere pocket change today. Eight years later, Mrs Edward Doheny, who had been living behind the building and was fed up with the frat-house racket, purchased the house for $70,000. She then bequeathed the home to the Sisters of St Joseph of Carondelet, an order part of the Roman Catholic Church (while the congregation’s origins go back to 17th-Century France, the Carondelet part comes from a town in Missouri). The Sisters used the home as a convent until 1969. For the next twenty years, the nuns allowed Mount St Mary’s College on Chester Place to use the house as a student residence. After returning to use as a convent, the home required a million-dollar restoration in the mid-90s due to damage sustained in the Northridge earthquake. You can see the landmark pop up in movies and TV shows now and then, including as the funeral home in Pushing Daisies.

I always wondered why the Stimson Residence wasn’t one of the first sites landmarked by the Cultural Heritage Board back in the sixties. Turns out it wasn’t for lack of trying. The first attempt at declaring the home an HCM happened in March 1965. The archdiocese resisted monument status to such an extent that it wasn’t until 1975 when the issue was again raised. Again, the archdiocese resisted, citing the designation would produce “undue restrictions on… [the] use and enjoyment of the property.” However, thanks mainly to a guy named Richard Mouck who really lobbied for dedication, the house of Stimson was officially landmarked in May 1979, a year after it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Finally, please see Don Sloper’s Los Angeles’s Chester Place for a bunch of interior photographs (and of this section of West Adams in general).

Sources:

“New Buildings.” The Los Angeles Times; Oct 20, 1885, 0_4

“Dynamite Fiends” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 7, 1896, p. 10

“Last Hope Gone.” The Los Angeles Times; Mar 18, 1897, p. 9

“Stricken Down.” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 1, 1898, p. 11

“Old Mother M’Garey.” The Los Angeles Times; Feb 4, 1898, p. 14

“Famous Figueroa St. Mansion to Be Converted to Convent” The Los Angeles Times; Oct 18, 1948, p. A1

Doherty, Jack “Castle Keep” The Los Angeles Times; Jan 2, 1994, p. 12

Sloper, Don Los Angeles’s Chester Place Arcadia Publishing 2006 Charleston, SC, Chicago, IL, Portsmouth, NH, San Francisco, CA

Cooper, Suzanne Tarbell, Don Lynch, and John G. Kurtz West Adams Arcadia Publishing 2008 Charleston, SC, Chicago, IL, Portsmouth, NH, San Francisco, CA

Up next: S.S. Catalina

continue reading...

Posted by

Floyd B. Bariscale

at

11:08 PM

18

comments

![]()

Labels: South Los Angeles

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)